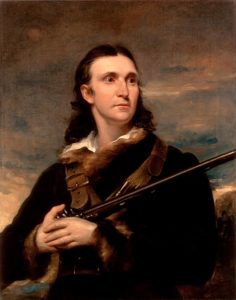

Recently, the McClung Museum debuted the miniature exhibition Masterful Mammals to showcase John James Audubon prints from our permanent collection. While Audubon is wildly known for his bird prints, the exhibition displays lesser-known prints of mammals from the McClung Museum collections. However, with the display of these prints, we must reflect on aspects of Audubon’s character that are not as widely known or discussed.

Nine Banded Armadillo, Dasypus peba, 1849-1854 Plate 146 from Viviparous Quadrupeds of North America, Vol. 3, New York John James Audubon (1785-1851) Hand-colored lithograph McClung Museum, Gift of Joel Rynning, 2010.10.44a

It has been well documented that Audubon held white supremacist views and enslaved at least nine people during his lifetime.

John James Audubon was born in Saint-Domingue (present-day Haiti) in the late 1700s. While many scholars have speculated about his heritage, research argues that Audubon was born to a plantation owner and a woman of Creole/African descent (Nobles 2017, John James Audubon: The Nature of the American Woodsman). At a young age, Audubon was sent to France to live with his father’s wife, Anne, where he developed an interest in nature, drawing, and the study of birds. At the age of 18, Audubon moved to a family-owned estate in Pennsylvania.

Although Audubon grew to be one of the world’s most celebrated artists and naturalists, he embraced white supremacist ideals and committed despicable racist acts throughout his lifetime. He bought and sold enslaved people, spoke out against emancipation, and unethically contributed to research to advance a white-dominant society. While messy and complex, it is necessary to address Audubon’s racist practices and critically examine his legacy when showcasing and discussing his work.

It is impossible to know if Audubon relied on Indigenous and local knowledge about flora and fauna to complete Viviparous Quadrupeds of North America (given most of the work for these volumes was actually done by his son), scholars have noted that Audubon relied on Indigenous and Black knowledge while completing his magnum opus, The Birds of America, as Native and Black peoples gave him information about where and how to find certain birds (Nobles 2017, John James Audubon: The Nature of the American Woodsman).

“The Runaway” Audubon, John James, and William Macgillivray. Ornithological biography, or An account of the habits of the birds of the United States of America; accompanied by descriptions of the objects represented in the work entitled The birds of America, and interspersed with delineations of American scenery and manners. [Edinburgh, A. Black; etc., et to 1849 i.e. 1839, 1839] Pdf. https://www.loc.gov/item/06018535/.

By calling attention to the problematic pasts of heroes of the art and natural history worlds, such as Audubon, we can recontextualize, redefine, and reexamine our understandings and relationships to these people. As a museum, it is our duty to contextualize the objects we showcase to present the whole picture. By addressing Audubon’s racist practices, we hope to move forward towards more equitable and ethical museum practices. by refusing to excuse his behavior or simply label him a “man of his time” as so many have done.

Further Reading:

https://www.audubon.org/news/the-myth-john-james-audubon

https://www.audubon.org/magazine/spring-2021/what-do-we-do-about-john-james-audubon