Figure 1. “Winter Corn” by Perry McKenna (CC BY 2.0).

Used by people around the world, corn is known by many names. The term maize actually derives from the Taíno word for corn, mahis: the Caribbean Taíno people introduced Europeans to this useful grain at the end of the 15th century. The Muscogee word for corn is “vce”; in the Cherokee/Tsalagi language, corn (also referred to as maize) is called Selu.

Selu is also the name of the Corn-Mother Goddess who provided corn to her people for nourishment. Cherokee histories tell of how Grandmother Selu came from Mother Earth. Grandmother was a human woman who supplied corn from her own body to feed her two grandsons. When the grandsons uncovered her secret, she died, but told her grandsons that she would be the Corn-Mother and gave them instructions: how to gather and harvest the corn that sprouted from her grave, how to plant the corn kernels from the cobs, and how to prepare and eat them for continued nourishment for years to come.

Many Native American tribes view themselves as children of the corn: corn has always been with them, and corn is a spirit of wisdom.

Figure 2. “Flint Corn Colors” by jlevnger (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0).

Characteristics:

Corn belongs to the Grass Family, Poaceae. The Grass Family species are all monocots, which means that they have only one seed leaf when they sprout. Other monocot characteristics include parallel veins in the leaves, horizontal rootstalks, typically simple branching, and floral parts usually in threes. The Grass Family is further characterized by knee-like nodes along the stalks and hollow flower stems.

Lacking showy flower petals to attract pollinators, grasses are actually wind-pollinated. The ovary matures into a grain or a single seed called a caryopsis, although sometimes in the Grass Family the ovary can mature into an achene or berry. The modified leaves, called bracts, are the part of the plant that protects the flower or seed; this chaff is also the part of the plant that is winnowed and harvested.

Corn is an annual grass, harvested in summer and fall. The plant has alternate leaves with newly formed ears also arranged alternately. Corn flowers, called tassels, are found at the top of the plant. Corn is harvested commercially for sugar, which is found in the roots at the base of the stalk. However, it is most notably harvested as a vegetable food or for pounding into flour. People have developed hundreds of varieties of corn, but there are six major categories: dent, flint, pod, sweet, flour, and popcorn.

Historical Uses:

Although corn has primarily been used as a vegetable food throughout history, it has also had other uses. The Cherokees have used corn medicinally by using “smut” (an edible fungus, Ustilago maydis) for salve, and parched grains for “long wind”, and to make an infusion used to treat “gravel” in the kidneys. Corn shucks have also been used by the Cherokees to create toy dolls.

In addition to eating the fresh kernels, Native peoples in the Southeast often dried corn and made it into hominy. The Muscogee (Creeks) and other Tribes enjoy “sofkey”, a thin soup made of corn that has a sour flavor. Other food uses elsewhere include fermenting corn into beer, using the flour formed from pounding the corn to make tortillas, using corn in soups and stews, and other variations of roasting, soaking, parching, and grinding. The corn smut, also known by its Nahuatl name huitlacoche, is a delicacy in Southwest and Central America, formed as moisture seeps in between husks on the ears of corn.

Additional medicinal uses of corn include utilizing the silks from the tops of the emerging ears, collected during the growing season, to make into a decoction that can be used for bladder and urinary tract infections, kidney stones, diabetes, and high blood pressure. Cornmeal has been known to treat diaper rash, rheumatism, and eczema. The dried corn cobs can also be soaked in water and rubbed on the skin to treat poison ivy.

Lastly, other parts of corn have also been utilized, including husks for wrapping tamales, or rolling smoking mixtures into dried husks for ceremonial purposes. Braided husks have also been used to make ceremonial masks, sleeping mats, baskets, and footwear. Among some Tribes, such as the Navajo, corn stalks have sometimes been used for thatching as well.

Archaeology of Corn/Maize:

In the archaeological record, corn is mostly recovered by paleoethnobotanists as fragments of corn kernels and corn cupules (the structure that attaches the kernels to the cob), and sometimes also embryos and glumes. However, occasionally corn cobs are recovered well preserved, such as the partial cob in the photo below from the Hiwassee Old Town site in southeast Tennessee.

Figure 3. Partial corn cob with kernels from the Hiwassee Old Town site (40PK3) Feature 300, Level 6 (Photo by Kelly Santana).

Through paleoethnobotany and plant genetics, researchers have uncovered that people domesticated corn nearly 9000 years ago from teosinte (Zea urians), a wild grass relative, although some think it may have also been crossed with other relatives. This hybridization occurred in Mesoamerica and spread throughout and into the Americas.

Corn passed along social networks from Mesoamerica to the American Southwest, across the Great Plains, and eventually into the hands of Southeastern farmers. Although the dating of corn introduction into the Midsouth has been debated and disputed over the years, it is evident in the paleoethnobotanical record that corn was a staple in the Southeast by at least the Late Woodland period, approximately 1100 years ago.

Corn heavily relies on the assistance of humans to grow and thrive. Native peoples grew numerous varieties of corn in efforts to minimize loss due to floods, droughts, or early frosts. They also often intercropped corn with beans and squash, together making up the “Three Sisters”. This mutual relationship allowed for the beans to be supported by the corn stalks, the beans to provide nitrogen to the soil, and for the squash vines and leaves to assist in keeping the ground moist and eliminating weeds.

For more information:

Check out our previous Plant of the Month posts on the Southern Foodways Garden, sunflowers, beans, and okra, as well as the following resources.

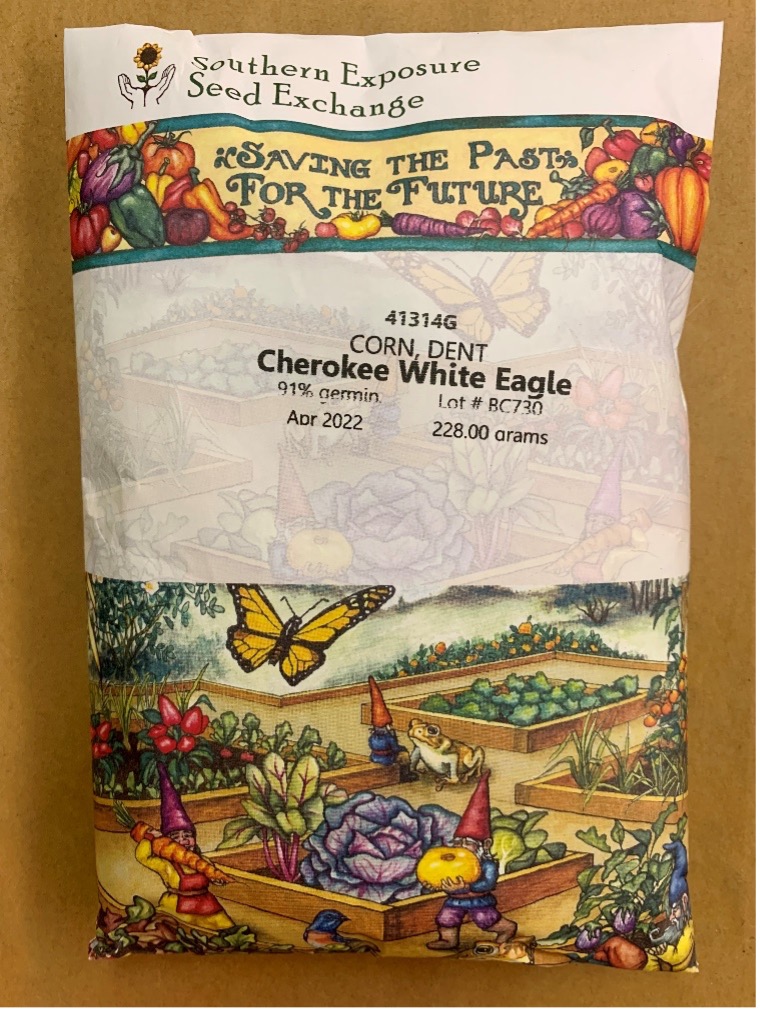

Heirloom varieties of corn can be found and purchased through organizations such as Baker Creek Heirloom Seeds, The Cherokee Nation Seed Bank (for tribal citizens only), Little Seed Library, Seed Savers Exchange (pictured below), Sow True Seed, and more.

Figure 4. Cherokee White Eagle Dent Corn, an heirloom variety, purchased from the Southern Exposure Seed Exchange (photo by Kelly Santana).

Awiakta, Marilou. 1993. SELU Seeking the Corn-Mother’s Wisdom. Fulcrum Publishing, Golden, Colorado.

Blake, Michael. 2015. Maize for the Gods: Unearthing the 9,000- Year History of Corn. University of California Press.

Hamel, Paul B., and Mary U. Chiltoskey. 1975. Cherokee Plants and Their Uses – A 400 Year History. Herald Publishing, Sylva, North Carolina.

Hudson, Charles. 1976. The Southeastern Indians. University of Tennessee Press, Knoxville.

Moerman, Daniel E. 1998. Native American Ethnobotany. Timber Press, Portland, Oregon.

Salmón, Enrique. 2020. Iwígara: The Kinship of Plants and People. American Indian Ethnobotanical Traditions and Science. pp. 73-77. Timber Press, Portland, Oregon.

Scarry, C. Margaret. 1993. Variability in Mississippian Crop Production Strategies. In Foraging and Farming in the Eastern Woodlands, ed. by C. Margaret Scarry, pp. 78-90. University Press of Florida, Gainesville.

Smith, Bruce D., and C. Wesley Cowan. 2003. Domesticated Crop Plants and the Evolution of Food Production Economies in Eastern North America. In People and Plants in Ancient Eastern North America, edited by Paul E. Minnis, pp. 105-125. Smithsonian Books, Washington, D.C.