Dancing Figure, 7th-8th century, Tang Dynasty, China, Earthenware with Straw Glaze and Pigment, Gift of Alan and Simone Hartman, 2003.6.18.

One of many wonderful things about working at a University museum is that there is a campus full of experts who often shed new light on our collections.

Some time ago, Dr. Suzanne Wright, Associate Professor of Art History at University of Tennessee and Chinese art expert, pointed out that we had misidentified a Tang Dynasty figure on display in our Decorative Arts gallery as being Middle Eastern.

Dr. Wright noted that the prominent curly hair and distinctive dress have led many scholars to identify these figures as dancers or drummers from Austronesia or possibly Africa.

It’s helpful to understand more about the Tang Dynasty period to know why many of their ceramics, including our example, depicted foreign travelers, traders, and immigrants to China.

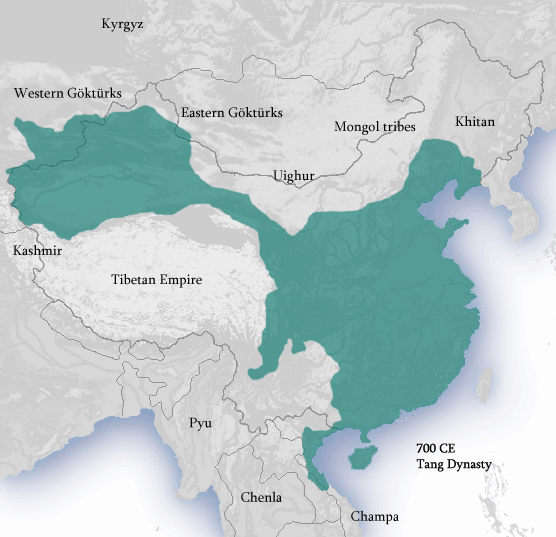

Tang Dynasty 700 CE from “The T’ang Dynasty, 618-906 A.D.-Boundaries of 700 A.D.” Albert Herrmann (1935). History and Commercial Atlas of China.

The Tang Dynasty, which lasted from around 618–907 CE, was a period of incredible political expansion and prosperity in China. The complex trade network known as the Silk Road linked linked the capital of ancient China, Chang’an (today known as Xi’an), to Persia, India, Indonesia, Korea, Japan, and many other areas in the Middle East and southern Europe. Travelers and traders brought new trade goods, fashions, and cultural norms to China, and China exported their own goods and ideas as well.

The Tang Dynasty was also an unprecedented moment for Chinese art. Economic prosperity and patronage of the arts led to a flourishing age for ceramics, painting, and poetry. Wealthy members of society and the royal court welcomed performers, both Chinese and foreign, as singers, dancers, and entertainers. Tang artists enjoyed depicting the many foreigners living, traveling, and trading in China during the time period.

Of all the Tang arts, minqi ceramics––earthenware “spirit goods” made for the dead––are perhaps the most well-known. Minqi depicted the foods, animals, and figures that provided “the deceased with entertainment, service, and guardianship.” Many minqi are earthenware sancai, or “three color” ceramics, skillfully decorated with yellow, brown, green, and occasionally blue glazes. However, not all tomb wares were tri-color sancai. The creamy white color on our collection’s figure at the top of this post was created by burning straw to make an ash glaze.

Curly-Haired Youth, Tang dynasty (A.D. 618–907), first half of 8th century, China, Earthenware with brown lead glaze, Art Institute of Chicago, Gift of Emily Crane Chadbourne, 1939.221.

The curly hair and pantaloons of the figure indicate that he is likely Malay. We cannot know the figure’s background, but scholars suggest that many of these minqi figures with curly hair and pantaloons depict black and brown-skinned Malay people of the South China Sea region, or more generally from South Asia, or even Africa. Despite being made in a mold, the figure displays remarkable detail. His stance suggests that he is a dancer, placed in a tomb to entertain the dead in the afterlife.

In our collection at the McClung, we hold a large number of Tang Dynasty minqi, or tomb ceramics––perhaps one of the finest collections in the Southeast. It is always exciting to learn more details about our own collections from experts on our campus, as well as from members of the public. We look forward to updating the label for our Dancing Figure in the upcoming months to reflect this new insight.

Additional Resources:

- Bindman, David, Suzanne Preston Blier, Henry Louis Gates, and Karen C. C. Dalton. 2017. The image of the Black in African and Asian art.

- Clydesdale, Heather Colburn. 2010. The vibrant role of Mingqi in early Chinese burials. Timeline of Art History. Met Museum.

- Hunter, Tavian. 2021. “Making connections: black people and cultures in Asia – British Museum Blog”. British Museum Blog – Explore stories from the Museum.

- LIM, Youngae. 2018. “The “Lion and Kunlun Slave” Image: A Motif of Buddhist Art Found in Unified Silla Funerary Sculpture”. Sungkyun Journal of East Asian Studies. 18 (2): 153-178.