July: Watermelon (Citrullus lanatus)

Although not native to North America, many of us link the summer months with watermelon (Citrullus lanatus), our July Plant of the Month. A member of the Gourd Family (Cucurbitaceae), watermelon is known for its sweet juicy fruit, with a glossy outer layer striped in two shades of green. Although we normally think of ripe watermelon flesh as being deep pink in color, the ripened flesh can range from red and pink to orange and yellow. Each fruit can contain 200 or more large seeds, which range in color from black to tan to white, yellow, or even red. Like other members of the Gourd Family, watermelons grow on vines that have tendrils and palmate leaves (with lobes and/or veins that spread out like hands).

Watermelon with leafy vine (“Big watermelon!” by trekkyandy, CC BY-SA 2.0) and slices of the red fleshy fruit (“Fresh sliced watermelon half and pieces on the table” by wuestenigel, CC BY 2.0).

The seeds provide our earliest evidence for their use, found at archaeological sites in Egypt and Lybia dating to around 5000 years old. Watermelon seeds have also been recovered from the tombs of pharaohs such as Tutankhamen (1323 BCE). Just as fascinating are drawings of watermelons in Egyptian tombs dating to over 4000 years old. Into the twentieth century, Egyptians consumed large quantities of watermelon in the summer months.

Images of watermelon from ancient Egyptian tombs (from Paris 2015)

Endemic to northern Africa, use of watermelons spread throughout the African continent and into the Mediterranean, and eventually through much of Eurasia. In the late 16th-century Spanish colonists first brought them to what is now the Florida and Georgia coast, where Native Americans quickly adopted them into their cultivated fields and passed them to other communities. Enslaved Africans also brought watermelon seeds with them to South America, the Caribbean, and the U.S. South, further spreading them throughout the New World.

Watermelons have been common constituents in gardens across the southern U.S. since the 17th century. Thomas Jefferson had watermelons planted at Monticello, but they were more common in the gardens of yeoman farmers and enslaved peoples than planters. Watermelons brought welcome variety to summer diets, often set in springs and creeks to chill and offered to visitors. They were also made into preserves and sweets that could be enjoyed during the off-season. A low-cost treat, watermelons are still sometimes referred to as “Depression hams” in the South.

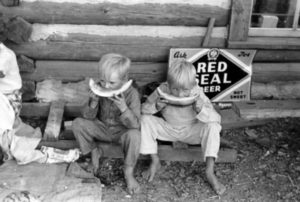

Two boys eating watermelon slices in Arkansas, 1937 (by Louise Boyle, in Southern Tenant Farmers Union Photographs collection at the Kheel Center, Cornell University).

Because of their connection with enslaved Africans, watermelons are often associated with southern foodways, and sometimes stereotypically with black people. This is in part due to the use of watermelons as a prop for “Sambo”, a derogatory image of a black boy that was pervasive in popular literature and advertising from the mid-19th century through the Jim Crow era of the 20th century. But Southerners have also used watermelon as a positive cultural symbol, in songs, art, recipes, and community gatherings, from festivals to seed-spitting contests. Hope, Arkansas, claims the title of Watermelon Capital of the South, offering “a slice of the good life”, while Cordele, Georgia, purports to be the Watermelon Capital of the World.

Several Native American tribes, including the Cherokees, chewed or made an infusion from watermelon seeds to treat kidney or urinary problems. African American folk practitioners also used dried watermelon seeds to remedy kidney stones, and a mash of seeds to expel worms.

But of course watermelon is most prized as a sweet, juicy, cool treat during the heat of summer. As Charles Wilson pointed out in his piece on watermelon in The New Encyclopedia of Southern Culture (2007), Mark Twain perhaps best captured the virtues of the watermelon in this passage from Pudd’nhead Wilson:

The true southern watermelon is a boon apart and not to be mentioned with commoner things. It is chief of this world’s luxuries, king by the Grace of God over all the fruits of the earth. When one has tasted it, he knows what the angels eat. It was not a southern watermelon that Eve took: we know it because she repented.

If you are looking for a different way to enjoy watermelon, you might try this recipe from Sheila Ferguson’s cookbook, Soul Food: Classic Cuisine from the Deep South:

Lillie-Mae Johnson’s Watermelon Rind Pickles

makes about 2 quarts

- 8 cups (3 lbs) of firm watermelon rind, trimmed and cubed

- 2 quarts limewater (2 teaspoons calcium hydroxide* dissolved in cold water)

- 2 ½ cups cider vinegar

- 1 cup water, more only if necessary

- 4 cups sugar

- 2 tablespoons ground allspice

- 6 inch cinnamon stick, broken into pieces

- 1 tablespoon whole cloves

- Mason jars

Scoop out or cut away all of the red flesh of the watermelon. Slice off all the dark green outer skin, leaving only the white rind. Cut the rind into 1 inch cubes until you have 8 cups.

Throw the cubed rind into the limewater in a large enamel or nonstick (not bare metal) pot and let it stand at room temperature for 4 hours.

Drain off the limewater and rinse the rind in fresh cold water. Leave it to soak for 20 minutes, then rinse again with fresh cold water. Do this at least 3 times, then cover with fresh cold water and bring to a boil. Turn down the heat and simmer until the rinds are fork tender, about 10 minutes. When done, remove them from the pot and leave to drain.

Mix the vinegar, water, sugar, allspice, cinnamon stick, and cloves together in the pot and bring to a boil. Lower the heat and simmer until the sugar is dissolved. Add the rinds and bring back to boiling, with additional water if there is not enough liquid to cover the rinds. Simmer the rinds for 10 or 15 minutes, or until they are clear and tender. Meanwhile sterilize the jars and seals with boiling water.

Pack the rinds into hot sterilized jars, using a slotted spoon so that you don’t get any of the spices into the jar (unless you want them in). After packing the jars, pour syrup almost to the top, leaving just under ¼ inch at the top of each jar. Seal tightly and store in a dark cool place.

*Note: Use calcium hydroxide (slaked lime) rather than calcium oxide (quicklime), which is corrosive until thoroughly wetted!

Resources:

Covey, Herbert C. 2007. African American Slave Medicine. Lexington Books, Lanham, Maryland.

Elpel, Thomas J. 2018. Botany in a Day: The Patterns Methods of Plant Identification. HOPS Press, Pony, Montana.

Feguson, Sheila. 1989. Soul Food: Classic Cuisine from the Deep South. Grove Press, New York.

Hedrick, U.P., editor. 1972. Sturtevant’s Edible Plants of the World. Dover Publications, New York.

Hilliard, Sam Bowers. 1972. Hog Meat and Hoecake: Food Supply in the Old South, 1840-1860. Southern Illinois University Press, Carbondale.

Moerman, Daniel. 2004. Native American Ethnobotany Database. Online document, accessed 8 July 2021.

Paris, Harry S. 2015. Origin and emergence of the sweet dessert watermelon, Citrullus lanatus. Annals of Botany 116(2):133–148.

Sokolov, Raymond. 1991. Why We Eat What We Eat: How Columbus Changed the Way the World Eats. Simon & Schuster, New York.

Wilson, Charles Reagan. 2007. Watermelon. In Foodways: The New Encyclopedia of Southern Culture, edited by John T. Edge, pp. 282-285. University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill.