The McClung plays a big role in the UT experience for many members of our campus community. To highlight these connections, we asked UT faculty and staff to tell us about an object in our collection that has impacted their classes, their students, or their own exploration within the museum.

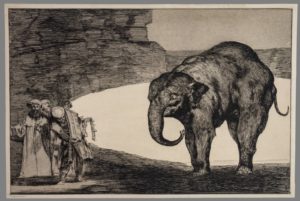

Tim Hiles, Associate Director of the School of Art and Associate Professor of Art History, has chosen one of the museum’s newer acquisitions. “One of my favorite pieces in the McClung Museum collection is the print entitled Disparate de Bestia by Spanish artist Francisco Goya. It is a remarkable print that has much to offer our students in technique, composition, and content. Beautifully crafted with etching, aquatint and Drypoint, this textured work demonstrates the great subtlety of which the print medium is capable. Additionally, the use of that texture to successfully juxtapose the form of the elephant on the right with the group of troubled figures on the left presents the opportunity for our students to understand how formal qualities inform content. Finally, the enigmatic subject matter, created during a time in the artist’s life of great reflection, provides a catalyst for our students to conduct research into its rich personal and political content.”

Tim Hiles, Associate Director of the School of Art and Associate Professor of Art History, has chosen one of the museum’s newer acquisitions. “One of my favorite pieces in the McClung Museum collection is the print entitled Disparate de Bestia by Spanish artist Francisco Goya. It is a remarkable print that has much to offer our students in technique, composition, and content. Beautifully crafted with etching, aquatint and Drypoint, this textured work demonstrates the great subtlety of which the print medium is capable. Additionally, the use of that texture to successfully juxtapose the form of the elephant on the right with the group of troubled figures on the left presents the opportunity for our students to understand how formal qualities inform content. Finally, the enigmatic subject matter, created during a time in the artist’s life of great reflection, provides a catalyst for our students to conduct research into its rich personal and political content.”

“Disparate de Bestia,” Fransisco de Goya, 1877, Etching, 2018.3.1.

This print, whose title translates to “Animal Folly”, comes from Fransisco Goya’s Los Disparates series created between 1815 and 1823. The series revisits Goya’s themes of the follies of human behaviour, and takes on a dramatic quality with their dark backgrounds, politically-driven content, and cryptic depictions of various proverbs. Though known as a painter in his time, Goya is now celebrated as one of the most important printmakers of his era. This print highlights the importance of the engraving as a communication tool for societal critique and communication.

In Disparate de Bestia, an elephant is confronted by four men, commonly identified as Moorish and Jewish politicians or lawgivers. The men hold a book (potentially of laws) and a collar of bells, and are attempting to keep the animal in a circus arena-like space. A common interpretation is that the Asian elephant, missing its tusks, represents “the people,” forced into accepting laws that will sap their strength and put them at the mercy of the ruling classes. During the reign of Ferdinand VII, commoners received different laws than those of the privileged classes.

The choice to depict Jews and Moors as the antagonizers in this image speaks directly to racist and anti-Semitic stereotypes that dominated Spanish society at the time. When Goya created this print, the Spanish Inquisition was coming to an end, but the distrust and hatred that it took advantage of and fostered against Jews and Muslims would persist far beyond the state’s formal persecution.

It is unclear if Goya was using the offensive visual language of stereotypes to showcase an overt personal prejudice. Goya was famously scrutinized by the Inquisition himself (see an entertaining fictionalization of his story in the 2006 movie, Goya’s Ghost). He was thereby extremely critical of the Inquisition and sympathetic to its other victims. He was also known to utilize biting satire to critique society and power structures. The history and artist, like this print, is complex and worthy of much discussion–which makes Disparate de Bestia one of the McClung’s best candidates for complex academic consideration.

Additional Readings:

- Douglas Cushing, Beyond All Reason: Goya and his Disparates, The Latest at the Blanton. Blanton Museum of Art, February 23, 2015.

- Melissa Doherty. The Plagues’ Contribution to the Spanish Inquisition, Yersinia pestis Essays (Insects, Disease, and History). Montana State University, Spring 2005.

- Anouar Majid. We Are All Moors: Ending centuries of Crusades against Muslims and other minorities, University of Minnesota Press, 2012

- Cullen Murphy. God’s Jury: The inquisition and the Making of the Modern World. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2012

- Andrei Pop. “Goya and the Paradox of Tolerance.” Critical Inquiry 44.2 (2018): 242–274.

- Wendy Thompson. The Printed Image in the West: Etching, Heilbrunn Timeline of Art. Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2003.