by Brett H. Riggs, Department of Anthropology, University of Tennessee

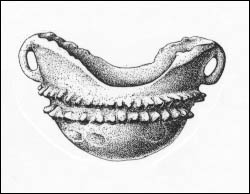

Figure 1. “Gravy boat” vessel.

An elaborate complex of fire ceremonialism is documented among a number of historic native Southeastern groups, including the Cherokees, Creeks, Chickasaws, Natchez, and Yuchis. Early accounts by Europeans indicate that fire was revered by many Southeastern groups as the embodiment of a supreme deity and document fire ritualism as a central component in annual cycles of native ceremonies. Southeastern fire ritualism continues today in the contemporary stomp dance grounds of Oklahoma. Like many aspects of Native American belief systems, it is difficult to project observations of such ritualism into the prehistoric past with confidence. However, two ceramic artifact forms, known colloquially as “gravy boat” pots (Figure 1) and “canoe” pipes (Figure 2), may represent specific evidence of fire ritualism in the Southern Appalachian region during the late prehistoric and protohistoric periods (ca. 1350-1600). A recent examination of “gravy boat” pots and “canoe” pipes in collections at the McClung Museum reveals a consistent pattern of stylistic similarity, and indicates that these unusual ceramic forms are essentially coextensive in their archaeological distribution.

Both artifact forms are uncommon, but consistently occurring, elements of late Mississippian archaeological assemblages throughout the Southern Appalachian province and its peripheries. Archaeological occurrences of “gravy boat” vessels and “canoe” pipes are documented from sites in the upper Savannah River, upper Oconee River, upper Chattahoochee River, and upper Coosa River drainage areas. Both artifact forms are represented from late Mississippian and Spanish Contact era sites in the Tennessee River drainage from the lower French Broad River downstream to northwestern Alabama. Both are associated with a number of different archaeological cultures and phases, and were, presumably, used by a number of different ethnic groups.

David Hally (American Antiquity 51:267-295), in a study of Mississippian vessel function, describes the “gravy boat” vessel form as:

…a small [.5-1.5 liters], slightly oval bowl with flat base, rounded sides, and slightly insloping rim. A large flange extends upward several centimeters from the rim at each end of the vessel and has a loop handle attached to its exterior surface….Exterior surfaces are…plain except for applique nodes that cover the upper portion of the vessel wall.

Hally suggests that these “gravy boat” vessels were containers for fire transport, and notes that vessel attributes such as the raised loop handles and nodes on the outer surface facilitate the handling of a hot vessel, while soot and spalls on the interior of “gravy boat” vessels indicate contact with hot, smoldering materials. Hally further notes that such vessels are recovered exclusively from burial and mound contexts, suggesting ritual associations. A number of ethnohistoric sources cite the use of ceramic vessels as ritual fire containers by Southeastern Indian groups.

John Howard Payne, who collected information on Cherokee traditions during the 1830s, provides an explicit description of “gravy boat” type ceramic vessels used to transport sacred fire (Payne Manuscript Vol 4:104-105, 225; emphasis added):

The priest made new fire…to be their guide and helper in the war….This fire he put in the sacred ark for the war. This…was about a foot long, shaped somewhat like a canoe, having a lid fitted to the upper side. All was made of clay, burnt in the same manner as Indian earthenware. No one must touch this, but the priest for the war, or his right hand man….It is said that these & the one who carried the ark would track their enemies in the dark, — could render themselves invisible when they pleased, — could walk barefooted on fire, or snow without injury….The [war] priest…carried the holy fire in the sacred vessel made for that purpose….It is generally six, or eight inches long, shaped like a trough, with a lid to cover it. It had handles at each end. It was however sometimes made like a pot, with handles on each side.

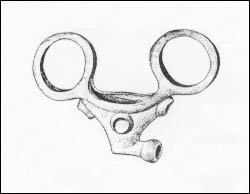

Figure 2. “Canoe” pipe.

The ritualistic functions of “gravy boat” vessels in fire transport can be inferred from their archaeological contexts, use wear and deposits evident on archaeological specimens, and ethnohistoric descriptions of similar vessels used in ritualistic transport of fire. Further evidence for the symbolic significance of the “gravy boat” vessels in late Mississippian contexts is the depiction of this form in late Mississippian “canoe” pipes (Figure 2), which exhibit a number of key elements of the unique pots.

The most realistic representations are ceramic elbow pipes with large shallow elliptical bowls, large rings at opposing ends, and 1-2 rows of applique nodes below the pipe lip. The elliptical pipe bowl is equivalent to the oval shape of the “gravy boat” vessel; the pipe rings represent the vessel handles; and the pipe nodes approximate the vessel noding. Other pipes are more conventionalized, with greater bowl height, slightly elliptical bowl orifices, attenuated rings on the bowl rim, and either low applique nodes, open circular punctations, or relief carved diamonds representing the vessel nodes. In some instances, effigies of raptorial birds adorn the pipe bowl. In both realistic and conventionalized forms, “canoe” pipes represent a transformation of functional vessel attributes into purely stylistic and symbolic elements of pipe ornamentation. Such pipes are abstractions of the “gravy boat” vessel form into a Mississippian iconographic symbol.

In addition to formal similarities, “canoe” pipes were functionally similar to “gravy boat” pots in that both were containers for fire in ritual settings. Ethnohistoric accounts document smoking pipes as vehicles for ritual offerings of tobacco and other substances in much the same way that offerings were consumed in open fires. Given the well documented ritual associations of the smoking complex in the southeastern United States, it is plausible that “canoe” pipes functioned, partially or wholly, in ritual contexts as images of “gravy boat” vessels. Formal characteristics of many “canoe” pipes, such as large (100 cc) bowl capacity, and elaborate, fragile appendages, render these pipes unsuitable for daily, private use. More likely, such pipes functioned in occasional public contexts such as group rituals.

Both “gravy boat” pots and “canoe” pipes can be interpreted as elements of a widespread ritual complex involving fire ceremonialism. The extensive distribution of both artifact forms across a number of archaeological cultures suggests that highly specific and detailed symbolic information was shared across social, ethnic, and political boundaries. This illustrates the permeability and probable fluidity of such boundaries in the prehistoric Southeast. In addition, these artifact forms point to the continuity of a tradition of fire ritualism from the prehistoric past to the present day among certain native Southeastern groups.