by Larry R. Kimball, Department of Anthropology, Appalachian State University

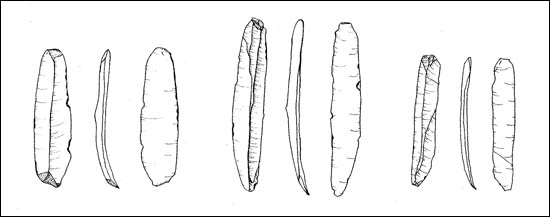

Hopewell blades (Figure 1) are small, elongate, unifacial (worked on only one side) stone tools flaked into very regularized forms. Hopewell blades are often made of Flint Ridge Chalcedony, whose only source is in south central Ohio. This area is also the heartland of the Ohio Hopewell culture (100 BC-AD 400), which is known for its involvement in an exchange network that included materials such as grizzly bear teeth, copper, silver, fossil shark teeth, mica, obsidian, and flint from the Rocky Mountains, the upper Great Lakes, the Gulf Coast, and the southern Appalachians. These exotic raw materials were used to make ritual items, which were deposited with the dead in specially prepared mortuary mounds. The involvement of social groups in the southern Appalachians in this Hopewell network is evidenced by the presence of Flint Ridge blades and Ohio ceramics at southeastern sites, and southeastern artifacts (Ridge and Valley flint blades, mica, quartz crystal, and ceramics from eastern Tennessee and western north Carolina) at Ohio Hopewell sites. A variety of functions have been proposed for Hopewell blades over the years, but this remains a matter of disagreement. These inferences, however, were based upon morphological characteristics and not observations derived from actual functional, or use, analysis.

Figure 1. Hopewell blades from the Garden Creek site used for meat cutting (left), fresh hide cutting (center), and sawing wood (right).

In order to learn more about the nature of this inter-regional exchange network, I have undertaken a functional study of Hopewell blades from two sites in the Southern Appalachians — Icehouse Bottom in eastern Tennessee and Garden Creek in western North Carolina. University of Tennessee investigations at Icehouse Bottom by Jefferson Chapman recovered a very large sample of blades (N=873). The vast majority (92%) of all blades are made of the immediately available Knox Black Chert. Blades of Flint Ridge Chalcedony represent 7% of the collection, and approximately 1% of the blades are of vein quartz. Icehouse Bottom is an open-air habitation site situated at a quarried outcrop of Knox Black Chert and on the first terrace of the Little Tennessee River, now inundated by Tellico Lake.

Seventy-nine Hopewell blades were recovered from the University of North Carolina excavations at Garden Creek. The majority of these specimens (73%) are of Knox Black Chert. Blades of Flint Ridge Chalcedony make up 25% of the collection. The remainder of the blades (2%) are of quartz crystal. These blades were recovered from an earthen mound and habitation areas.

The method by which the function of stone tools can be determined is called microwear analysis. Microwear analysis is an experimental approach to the study of stone tools based upon the observation that the edges of stone tools will develop microwear traces during tool use. Microscopic characteristics of these wear traces vary according to the kind of material worked. The technique employs a binocular incident-light microscope, as opposed to the more commonly known stereomicroscope. The incident-light microscope features a system of illumination which permits inspection of microtraces at magnifications from 50x to 500x. These microtraces are compared to those present on replica tools which have been used experimentally for different tasks. The identification of microtraces in this study was made by reference to a collection of approximately 200 experiments conducted by the author.

The results of the microwear analysis to date indicate that over 85% of the Hopewell blades exhibited microwear traces. A variety of tasks were identified:

- Light butchery, meat cutting

- Hide cutting, bone/antler working — sawing, graving, planing, and boring

- Wood whittling and sawing

- Cutting/incising soft stone — mica or soapstone.

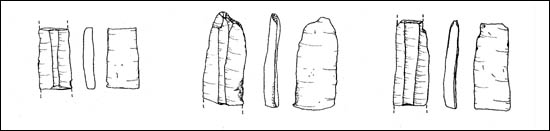

In addition, 30% of these blades were used for more than one task. Thus, we can infer that Hopewell blades were not special purpose tools. Furthermore, it appears that these blades were designed (Figure 1) so that they could be used initially in one manner (butchery, wood working, hide cutting, or bone/antler sawing) and then intentionally broken (Figure 2) to use the strong, perpendicular edge to grave or incise very hard materials like bone and antler.

Figure 2. Snapped Hopewell blades from the Garden Creek site used for sawing and graving bone/antler (left), dry hide cutting and bone/antler sawing (center), and soft stone cutting and graving and planing bone/antler (right).

This latter use and form is called a burin, and has never been documented for Hopewell blades in eastern North America. Another novel discovery is the documentation of the use of at least two Hopewell blades to cut or incise soft stone (Figure 2, right). Interestingly, both of these soft stone-working blades were recovered at Garden Creek, which is situated in a locality rich in both soapstone and mica.