“If we can hold Chattanooga and East Tennessee, I think the rebellion must dwindle and die.”

– President Abraham Lincoln to General William S. Rosecrans, telegram, October 4, 1863

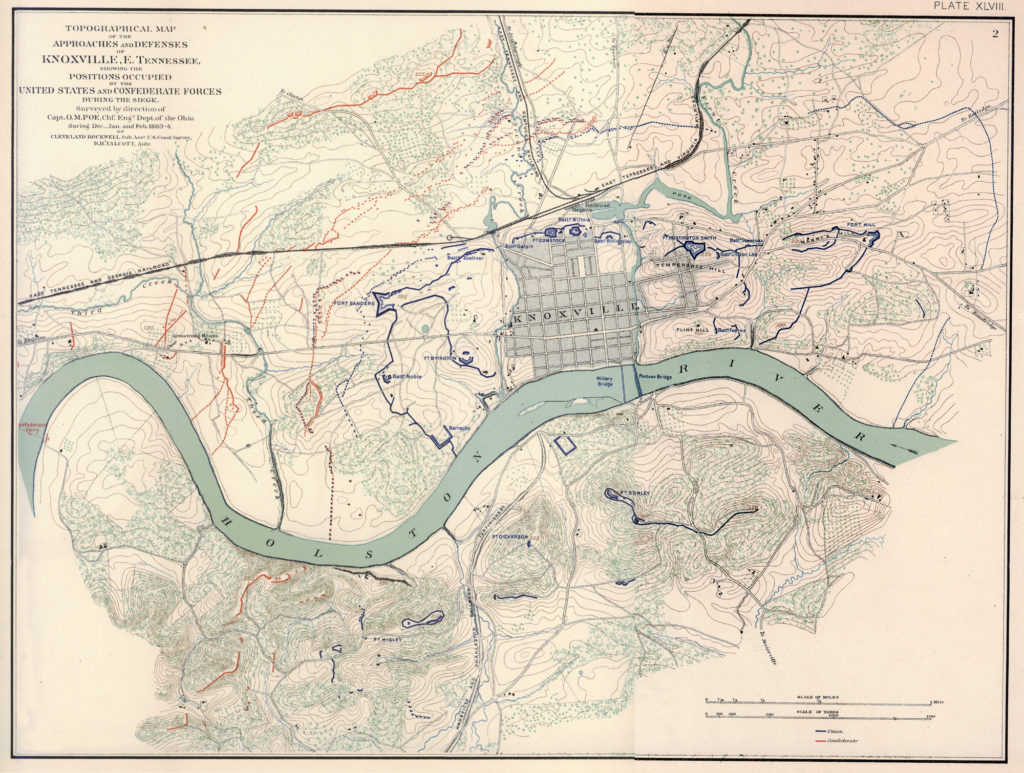

Orlando Poe Map Adaptation byCartography Shop Department of Geography, UTK Charles A. Reeves, Jr.

War was declared in April 1861. In early June the state of Tennessee voted to secede from the Union. While Tennessee was a slave-holding state, East Tennessee’s natural geography prevented the establishment of large plantations that required vast amounts of manpower. Farms were small and those that enslaved people usually had fewer than ten.

Knoxville was a thriving town of some 4000 people, including roughly 400 enslaved people. These were owned primarily as domestic servants by Unionists and Confederates alike, but the local economy was not dependent on enslaved labor and was not strongly aligned with the larger Southern slave economy.

East Tennessee was of vital importance to both sides due to several unique assets: abundant livestock and crops; minerals and blast furnaces for manufacturing weapons; and the railroad, running from Richmond to Atlanta, which transported armies and provisions. Yet neither side could count on the consensus and loyalty of the population, so divided was its allegiance.

In July 1861, Confederate troops arrived. From then on, Knoxville was occupied for nearly every day of the war. On September 3, 1863, shortly after the Confederates withdrew to reinforce General Braxton Bragg in Chattanooga, Union General Ambrose Burnside and the Army of the Ohio rode unopposed into Knoxville.

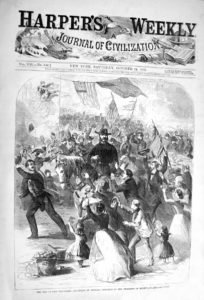

HARPER’S WEEKLY: A JOURNAL OF CIVILIZATION / October 24, 1863 / Original magazine cover / Museum Purchase / The woodcut illustrates in an almost mythical style Union General Ambrose Burnside’s triumphant entry into Knoxville. Burnside was cheered as a liberator by the many Unionists who had been living under Confederate rule for two and a half years. This was the high point of Burnside’s controversial military career.

ABRAHAM LINCOLN (1809-1865) / Photograph of original oil painting by F. A. Lackner, 1948 / Gift of Alvin Ukman, 1982 / From the start of hostilities President Lincoln had been acutely aware of the Unionist sentiment in East Tennessee and the suffering of the people because of it. He regularly urged his generals to go to the relief of the loyal mountaineers. / “My distress is that our friends in East Tennessee are being hanged and driven to despair, and even now are thinking of taking rebel arms for the sake of protection. In this we lose the most valuable stake we have in the South.” Lincoln to General Don Carlos Buell, telegram, January 6, 1862

WALKING STICK / 1863 / Hickory / Loaned by Lincoln Memorial University, Abraham Lincoln Museum, Harrogate, TN / The carved walking stick features a grip of an eagle killing a copperhead snake. “Copperhead” was a term used during the war to describe Northerners with anti-war, pro-Confederate sentiments. / Seven knots bear the carved letters L-O-O-K-O-U-T. The plate on top reads: / “To Abraham Lincoln, President of the United States from B. Frank Winchester, Maryland, Capt., VCS Vols from the field of Battle, Lookout Mt., Nov. 24, 1863”

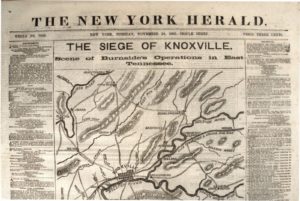

THE NEW YORK HERALD / November 24, 1863 / Original newspaper, front page / Museum Purchase / The eyes of the nation were on East Tennessee during the late fall of 1863. The headline and excellent half-page map illustrate how significant the “Knoxville Campaign” was to the news-hungry public. “Burnside still holding out. Burnside declares he will certainly hold Knoxville,” the inside text states confidently.