Assumed by many to be predominantly associated with Appalachian “hillbilly” culture and the folk revival in the Northeastern United States, it may come as a surprise to find that the banjo— the proverbial “white-man” mountain instrument—was developed centuries ago by enslaved Africans in the North American and Caribbean colonies.

The earliest banjos were played exclusively by the enslaved at least two hundred years before whites ever considered laying hands on what was, to the slaveholding culture, a “primitive” instrument. By the beginning of the nineteenth century, this negative perception began to change, and by mid-century white musicians had adopted the banjo in minstrel shows, catapulting it into mass production in the last half of the century. The banjo is now mostly known for its role in bluegrass music, overshadowing its historical origin and its place of prominence as an African American contribution to American music. It is this origin and early history of the banjo that is the focus of this exhibition.

- African American musicians in minstrel line, c. 1860s, albumen print. Courtesy of Jim Bollman.

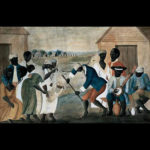

- The Old Plantation, watercolor painting, c. 1790–1800. Courtesy of Colonial Williamsburg.

- African Xalam

- (top) “Old Plantation” gourd; banjo, c. 2005, length 35 in. Courtesy of Pete Ross, maker; (middle) Philadelphia Centennial banjo, c. 1876, length 37 in. Collection of Jim Bollman; (bottom) Senegalese xalam, c. 1850, length 25 in. Collection of Peter Szego.

- Levi Collins, courtesy of Museum of Appalachia. Photographer: Robin Hood.

- Fretted instrument ensemble. c. 1896, courtesy Jim Bollman.

- Henry C. Dobson/Martin Bros. Banjo, c. 1868.

The African Roots of the Banjo

The majority of Africans brought to the North American and Caribbean colonies as slaves came from West Africa, and it is to this region that historians and folklorists turn in searching for antecedents of traditional African American musical forms. Banjo-like lutes have been described in West Africa for at least seven hundred years, and oral histories suggest that lute playing may have been practiced centuries earlier. Contemporary musicologists have documented the amazing variety of musical expression and instrument manufacture that exists in West Africa today, much of which bears a clear resemblance to historical traditions in the Americas.

The materials used to build these lutes—including gourds, wood, twine, and animal hide—are the very reason that the earliest instruments no longer exist—they have simply decayed. What does exist is a handful of written descriptions of African instruments in journals, travel logs, and slave-trading documents.

West African lutes of today are made in many shapes and sizes, and go by names like kora, n’goni, xalam, and akonting. Examples of these instruments, dating from 1850 to the present, illustrate the African origin of the banjo.

The Earliest Banjos in America

Enslaved Africans began arriving in the Caribbean in the early sixteenth century very shortly after the European discovery of the Western Hemisphere. Historical writings suggest that music and dance were encouraged on slave ships for exercise, and that African instruments, including the “banjer,” were used to provide this music. Instruments were also made in the New World, based on those that the musicians knew from their homes across the Atlantic Ocean.

In 1654, traveler Adrien Dessalles provided us with the earliest description of a banjo-like instrument in the Americas, noting that the banza was used to accompany dances in Martinique. Among the earliest extant banjos from the Americas is a banza from Haiti (the word is still used in Haiti to describe the instrument) dating to the early 1800s, which is currently housed in a Paris museum. Historian and instrument builder Pete Ross has studied this banza and makes precise reproductions thereof, one of which is in the exhibit. It is quite similar to West African lutes, but has a flat, rather than round, fingerboard (like a guitar), likely evidence of European influence on the instrument’s structural evolution in the Americas.

Paintings, drawings, and written descriptions provide historians with a surprisingly accurate idea of what the earliest banjos looked like. They had names like banza, banshaw, strump-strump, and bangie. Pete Ross and fellow luthier/historian Jeffrey Menzies research and recreate these gourd banjos from the visual and written evidence available. Some of these exhibited are replicas of those played centuries ago; some are contemporary revisions of the old style. All of them are living reminders of a vast and largely lost dimension of American musical history — and, yes, they are all quite playable, wonderful-sounding instruments.

The Rise of the Minstrel Show

In contrast to the relatively undocumented period of early African American music history, we know much of the era in which whites in the United States became enthralled with the banjo. This period of time, from the 1830s to the early 1900s, is often referred to as the “minstrel era.” In the minstrel show, white players would smear burnt cork on their faces, dress in outrageous clothing, don a banjo, tambourine, and fiddle, and “act the fool” on stage for an adoring audience. From the late 1860s to 1890s, black minstrel troupes also formed, but audiences preferred “Jim Crow” acts to authentic performances, further relegating minstrel performances to the realm of comedy at the expense of historical and cultural accuracy.

The minstrel show was the first American pop music—indeed the first American mass entertainment, and it was wildly popular, particularly among the working people of northern urban areas. Despite the legacy of racism associated with the minstrel show, historians who study this period have, as a result of its popularity, volumes of written music, dozens of instruments, concert advertisements, and more at their disposal. We are able to know much of the music that came before the minstrel show (early African American music) by observing the earliest imitations of it.

Handmade banjos began to give way to mass-produced instruments as the minstrel craze grew. Makers like George Teed, James Ashborn, and William Boucher Jr. capitalized on public interest by producing affordable instruments for the aspiring banjoist and deluxe instruments for those who could afford them. In addition to banjos, products of all sorts, including toys, pottery, and clothing were produced in response to the minstrel phenomenon, which also swept European cities. Included in the exhibition are a variety of banjos and ephemera from this era from the collections of Peter Szego and Jim Bollman.

From the Minstrel Stage to the Victorian Parlor

As public interest in the banjo grew, so did the ways it was applied musically and produced structurally. Even as the crude minstrel show was taking the world by storm, performers and instructors began to introduce an increasing variety of songs and playing techniques to the white banjo-playing public. More intricate songs required more intricate instruments. Patents for innovative and often unusual designs began to increase as makers tried to keep up with public demand.

Growth in public interest and diversification in playing style were the primary catalysts for change in banjo design in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Less noble were the attempts by some banjoists and banjo makers to “elevate” the banjo from its “primitive” origins, by emphasizing non-minstrel styles of music in marketing the banjo to the growing white middle-class public. Some of these attempts to popularize the banjo to all classes of society included denying its African origin.

Impossibly ornate banjos characterized the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Modern designs, intricate inlay patterns, and innovative features streamed through the US Patent Office. Much of the music being played on these instruments came from the classical repertoire, and banjos could be found in the finest of New England parlors. Banjo clubs and orchestras performed for ladies and gentlemen in gowns and tuxedoes, a far cry from the slave quarters of the relatively recent past. Selections from the collections of James Bollman and David Ball testify to this amazing flowering of innovation, the era in which the finest banjos in history were made.

Hillbillies and the Banjo

As the popularity of minstrelsy and classical banjo raged in the urban areas of the American Northeast, black and white musicians in the Appalachian Mountains and the Piedmont Carolinas developed their own uses for the banjo. Appalachian social music was played for dancing and less formal public entertainment. The mingling of northerners and southerners, city dwellers and country folk, brought about by the Civil War, allowed the introduction of minstrel tunes to the Appalachian songbook, many of which survive today. Some early twentieth-century banjos along with a few more contemporary designs, courtesy the Museum of Appalachia, are displayed.

The Twentieth Century and Beyond

Theories abound as to the question of the disappearance of African American banjoists. Certainly, the ridicule associated with the minstrel show (the banjo being its pivotal instrument) drove many black musicians to choose another, perhaps less stigmatized instrument, such as the guitar. The first decades of the twentieth century brought Americans a new musical craze—jazz—and many black banjo players simply followed the national trend. The banjo was the only stringed instrument loud enough to be heard above the horns and drums that characterized jazz music. (Only with the advent of amplification did guitars appear in jazz.)

Today, the banjo is prominent in bluegrass, a new interpretation of hillbilly music. Banjoists from both the jazz and bluegrass traditions have done well in preserving the banjo and presenting it yet again to music fans worldwide. Jazz and bluegrass are, however, outside the scope of this exhibit with its emphasis on the early history of the instrument.

As we have seen, American music is fluid and dynamic if it is anything at all. Time can only tell where the banjo will appear in the future, who shall hold it, and who shall preserve it. Recent interest in the banjo and the musical traditions that include it certainly bode well for this instrument, and rightly so. The banjo has been in this country since the 1600s, and it has defined and been defined by some of the most significant events and attitudes in this nation’s history. The American love affair with the banjo has taken many turns and, as a response to new research into the history of the instrument, the banjo shall be understood more deeply and completely than ever before.

Many thanks to exhibition curator, Matt Morelock, as well as to the exhibition lenders: Museum of Appalachia, David Ball, James Bollman, Ulf Jägfors, Jeffrey Menzies, Pete Ross, and Peter Szego. Exhibition sponsors are: First Tennessee Foundation, Lucille S. Thompson Family Foundation, MetroPulse, Tennessee National Alumni Association, State of Tennessee, UT Office of the Chancellor, Pilot Corporation, WBIR-TV, and WDVX-FM.