Bridging Time Through Letters: Insights into Everyday Life in the 1800s

Written by Graduate Research Assistant Madison Fogle

It can be really easy to think of the past as something distant and separate from our own lives. Sometimes, it feels like generational differences can be this huge divide, and the farther back in history, the farther removed we feel from the people who lived then. But despite changes in culture, technology, and time, people are still… people.

The 1830s and 1840s were hugely transformative for the world and for England. Uprisings and revolutions, the rise of imperialism, and a booming economy characterized the 1830s, leading to the beginning of the Victorian Era in the United Kingdom in 1837 with Queen Victoria’s monarchy. These people were living in a time of rapid changes in their culture.

In 1953, Mr. and Mrs. Kenneth Haws donated archival materials to the McClung: letters, receipts, and prayers that allow us to take a deeper look into the minds of people living in the past. Surprise: we have more in common than you think. What better way to understand people’s personal lives than their own words?

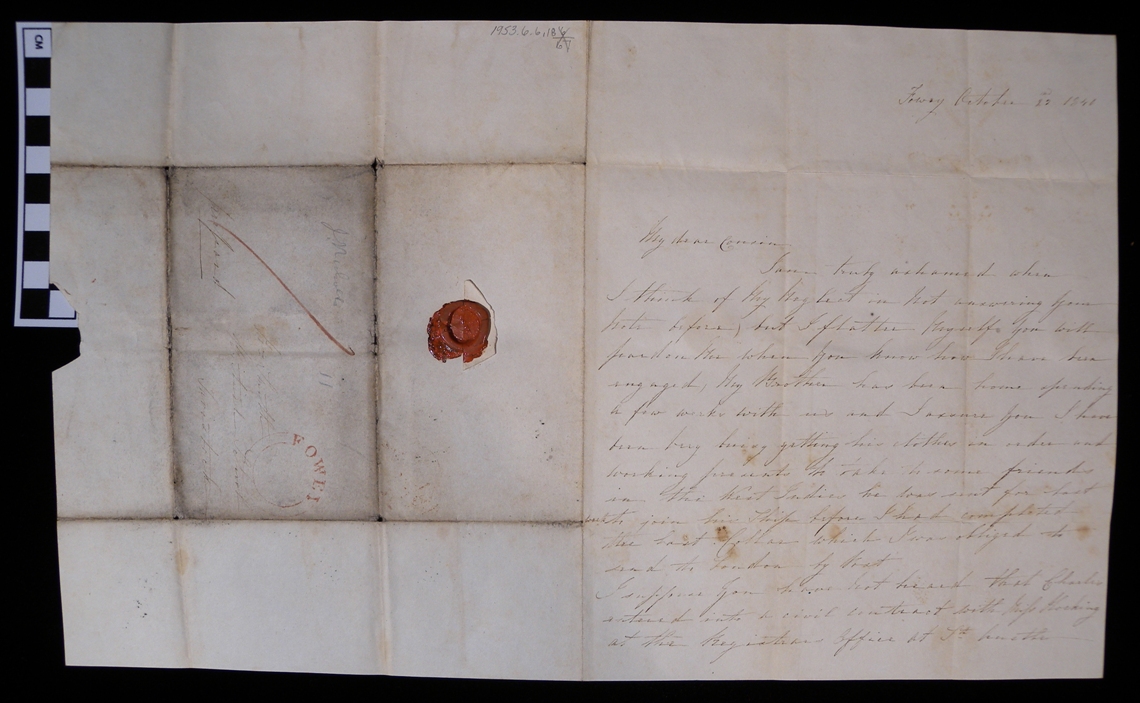

The telegraph system was invented in 1837, and by the end of the nineteenth century, thousands of telephones were in service in England. But until that point, friends had to rely on writing letters in order to stay in touch. It’s hard enough to answer that text from your mom or respond to that email still sitting unopened in your inbox. Taking the time to sit down and write a letter to a friend was just as easy to put off, maybe more so since they didn’t have that pesky red notification bubble following them around. Many of the letters in this collection contain an apology as a greeting. One person writes, “I am truly ashamed when I think of my neglect in not answering your note before, but I flatter myself you will pardon me when you know how I have been engaged…” (1953.6.6.18). Then they go on to complain about how their brother is home.

(1953.6.6.18) Handwritten letter with red postmark and complete wax seal. Dated October 22, 1840 and addressed to “Miss Smith / British School / Tavistock.”

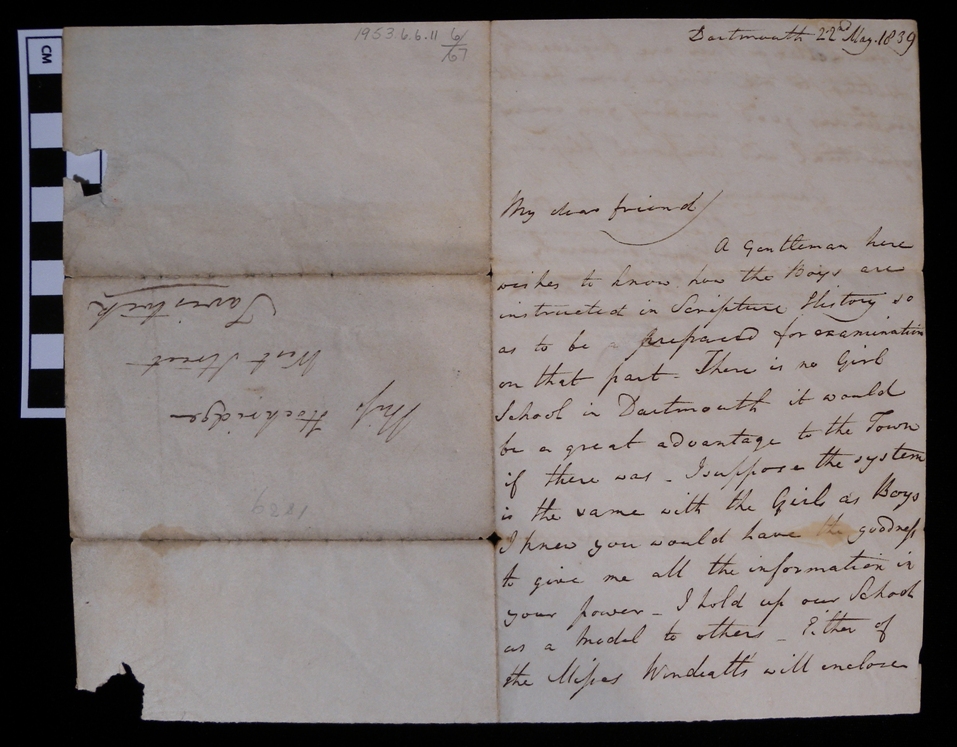

Many of the letters in this collection are addressed to women working at the British School in Tavistock, a small town in West Devon, England. One letter to the head of the school, Miss Hockridge, states, “There is no Girl school in Dartmouth it would be a great advantage to the town if there was – I suppose the system is the same with the Girls as Boys…” (1953.6.6.11). The women’s suffrage movement in England wouldn’t really kick off until the late 1850s, nearly twenty years after this letter was written, but this letter shows how women thought about the treatment of young girls and the opportunities they lacked.

(1953.6.6.11) Handwritten letter written in England dated May 22, 1839 addressed to “Miss Hockridge / West Street / Tavistock.”

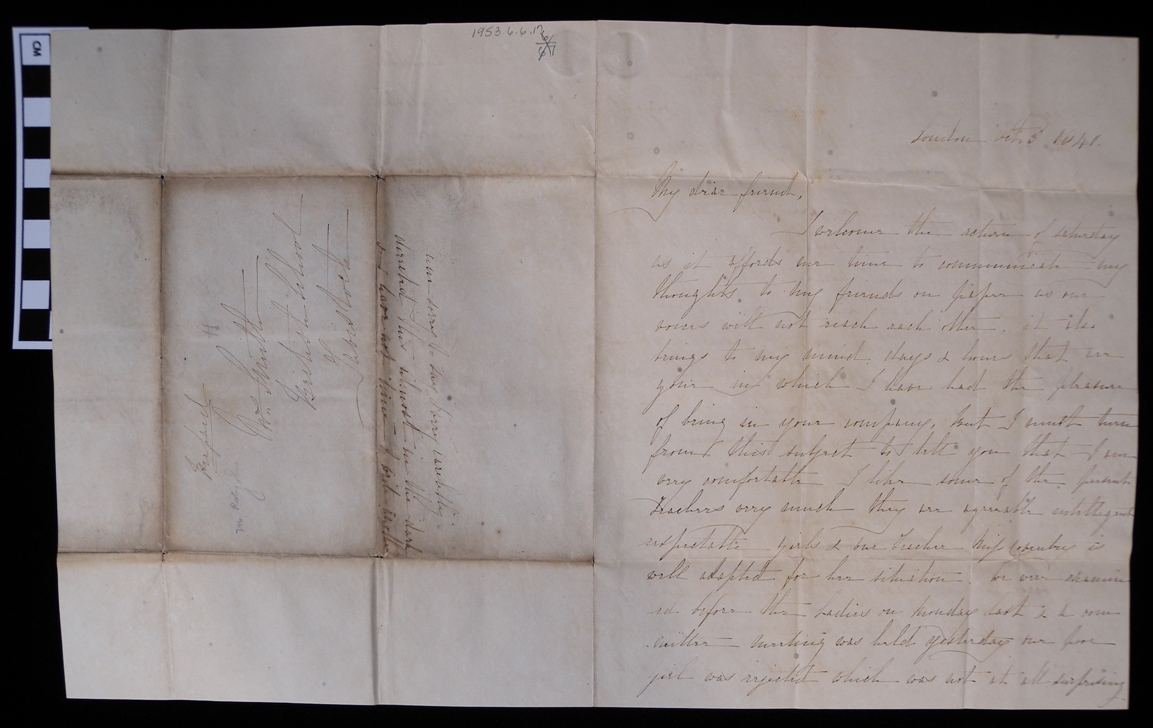

Another letter, addressed to Mrs. Smith at the British School, states, “My dear friend, I welcome the return of Saturday as it affords me time to communicate my thoughts to my friends…” (1953.6.6.17). The weekend we have now wasn’t truly established until the early twentieth century, but the push for designated leisure time began in the 1840s, according to historian Brad Beaven. The person writing this letter obviously had some form of free time on Saturdays instead of the rest of the week, showing the beginnings of what would become the weekend.

The people who wrote these letters are long gone, and the world has changed exponentially since they were here two hundred years ago. But, still, it does them and us a disservice to think about them as completely different from us. In a world of extreme cultural and political changes, daily life went on, and people still complained about their brothers.

(1953.6.6.17) Handwritten letter with a watermark dated October 3, 1840 written in England and addressed to “Mrs. Smith / British School / Tavistock.”