Figure 1. “Arundinaria gigantea 3zz” by David J. Stang (CC BY-SA 4.0).

Often confused with bamboo, rivercane is a native resource that has been used for thousands of years, most notably in basketry. But how do you tell this native plant from its non-native counterpart? To tell rivercane apart from other introduced bamboo species, you must pay attention to size, branching patterns, and the stems of the plant. Native rivercane is typically less than one inch in diameter and only grows between six and fifteen feet (if taller, it has been growing for decades!). Native rivercane also has angled branches (almost parallel to the stem) occurring at each internode, and adds a new branch each year. Comparatively, non-native bamboo often has stems exceeding one inch in diameter and reaches heights over thirty feet. Non-native bamboo also has perpendicular branching and a groove called a sulcus along one side of the stem between nodes.

Characteristics:

Arundinaria gigantea (more commonly known as rivercane, giant cane, or canebreak bamboo) is a member of the Poaceae or Grass family and is native to the central and southeastern United States. Rivercane can be found near any low-energy river or stream and is quite adaptable to varying altitudes. The dense grouping of rivercane, called a “canebrake”, is a monoculture that provides food and shelter to many wildlife and also prevents soil erosion with their root networks along riverbanks. The stalks visible above ground shoot up from horizontal roots. The plant can grow upwards of twenty-five feet, but typically grows between eight and twenty feet high.

Unfortunately, cattle have overgrazed native rivercane, and many patches have been depleted. In western North Carolina, the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians (EBCI) have been working to reconstruct and protect rivercane for traditional uses. The Cherokee Preservation Foundation has provided funding through the Revitalization of Traditional Cherokee Artisan Resources (rtcar.org). The areas where rivercane grows are monitored closely, with competing saplings removed. Mowing nearby is also avoided as it would limit the cane growth.

Historical Uses:

Figure 2. “ River Cane for Baskets, Cherokee Camp, Colonial Williamsburg” by sarahstierch (CC BY-SA 2.0).

Cane has been used historically for a wide variety of purposes, especially by Native American tribes and Indigenous communties. The Houma have used cane roots medicinally as a kidney aid and utilized the young shoots to make arrow shafts. The Seminoles have also used the plant medicinally, making a decoction of the root to be used as a cathartic. They also utilized the plant to make blow guns, knives, arrows, war spears, and bows, but have additionally made flute instruments and blowing tubes for working melted silver. The Choctaws have used cane in basketry as well as to make blowguns and darts. The Cherokees have used cane in basket-making, for building material to create dwellings, as fuel, for knives and tools for small-game hunting, to make candles, and also to make flutes from the “joints of the reed.” Young shoots of rivercane can also be cooked and eaten as a green. Figure 2 depicts the process of using cane for weaving baskets.

Archaeological Cane:

Cane can be found in the archaeological record, and is often found carbonized from Southeastern sites after it has been exposed to fire and preserved. Figure 3 shows a fragment of well-preserved rivercane basketry from the Toqua site (40MR6) in Monroe County, Tennessee. However, most commonly, small cane fragments will be recovered from archaeological contexts. Upon first glance, the small fragments of cane typically found by paleoethnobotanists can be confused with wood charcoal, but under a microscope there are multiple diagnostic markers that can differentiate the two.

Figure 3. Rivercane matting from Toqua site, 40MR6 (photo by Kelly Santana).

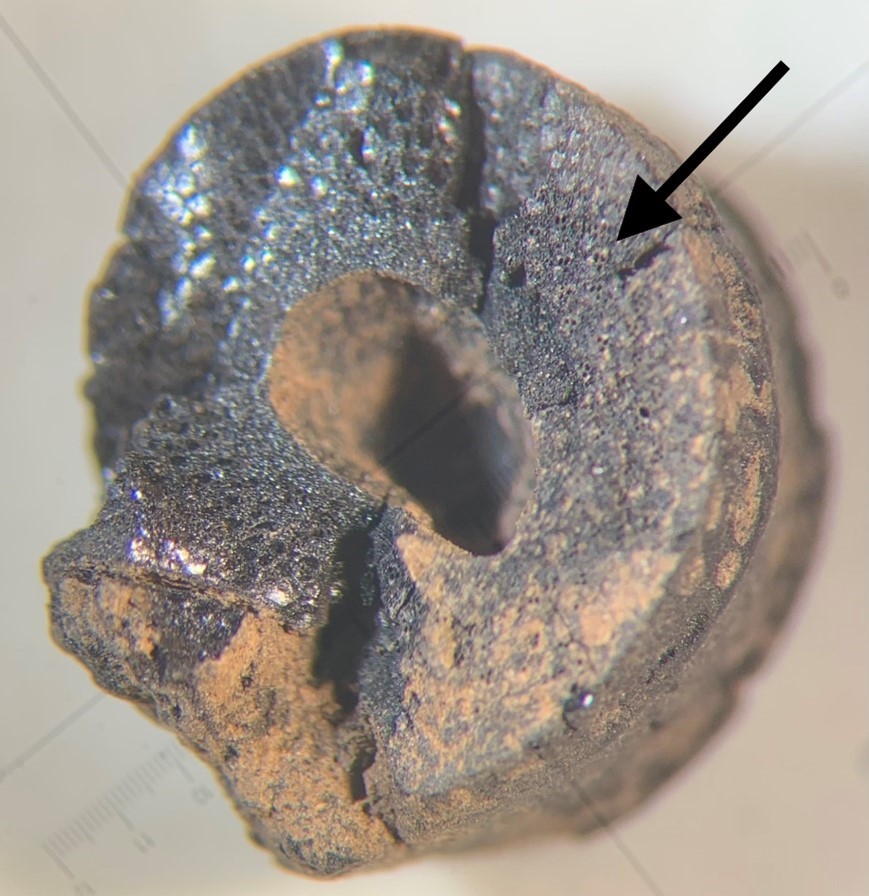

Primary among these are the linear vascular bundles running the length of the cane that are indicative of a monocot plant. These small vascular bundles are often referred to as “paw prints” when viewed in a cross-section of the cane. Figure 4 shows a small fragment of archaeological cane under a low-powered microscope exemplifying this diagnostic feature.

Figure 4. Archaeological cane fragment from under the microscope with arrow pointing to diagnostic feature of “paw-print” vascular bundles (photo by Kelly Santana).

For More Information:

Duggan, Betty J. and Brett H. Riggs. 1991 Studies in Cherokee Basketry. The University of Tennessee Publications Center. Knoxville, Tennessee.

Hill, Sarah H. 1997. Weaving New Worlds: Southeastern Cherokee Women and Their Basketry. The University of North Carolina Press.

Lane, Rose Jenkins. 2021, June 23. “A New Day for Rivercane”. Conserving Carolina. https://conservingcarolina.org/rivercane-restoration/

Moerman, Daniel E. 1998. Native American Ethnobotany. Timber Press, Portland, Oregon.

NC State Extension Gardener Plant Toolbox. https://plants.ces.ncsu.edu/plants/arundinaria-gigantea/

US Department of Agriculture, Natural Resources Conservation Service. 2021. PLANTS Database. Electronic document, https://plants.usda.gov/home