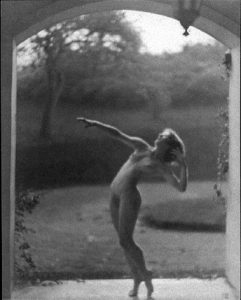

Harriet Whitney Frishmuth, with The Dancers (1921) and The Star (1918). Unknown date, unknown photographer. Special Collections Research Center, Syracuse University Library, Syracuse, N.Y.

Early Life

Frishmuth was born in 1880 in Philadelphia to a family of physicians. It is thought that this early exposure to anatomy may have influenced her interest in the human form later in life. Frishmuth moved to Europe early in life with her mother and sisters, where she would study in both France and Germany. During this time in Switzerland, she first explored her interest in sculpture. Her first work would be a bust of her mother, sculpted entirely from memory.

At the age of 19, Frishmuth moved to Paris to further pursue studies in the arts. While there, she enrolled in a class with Auguste Rodin, who, although having brief contact with her, would prove to be one of the most influential mentors of her early life. Rodin emphasized the importance of human movement in his teachings, and Frishmuth took note. Her best-known sculptures that she would later create were heavily influenced by dance.

Dance as a Muse

Following her studies in Europe, Frishmuth returned to New York, where she enrolled in the Art Students League. She also continued to study dissection and human anatomy at the College of Physicians and Surgeons. In 1913, Frishmuth purchased a house and studio at Sniffen Court. Over the next twenty years, this would serve as the backdrop where she would produce her most significant and well-known work. It was here that Frishmuth first met Desha Delteil, a young Yugoslavian ballet dancer who was also making a name for herself. Delteil would go on to inspire Frishmuth’s work for the next several years, serving as her main muse. Of their first meeting, Frishmuth recalls the following in an interview:

Extase (Nocturne), Harriet Whitney Frishmuth, 1920, Bronze, Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art

It was in 1916 that Desha knocked at my studio door in Sniffen Court and asked if I could use her. I liked her attitude right away but I didn’t have time just then. I took her name and address and told her I would let her know when I could work her in. When we had finished our little chat she went out skipping, half dancing and singing through the courtyard to the street. That was the beginning of a very pleasant relationship between Desha and me. She posed for me for years and is the model in ninety percent of my more important work. At first I used her for my class of five or six pupils. Then one week I had her pose just for me and as neither of us knew exactly what we wanted I put record on the Victrola. It was L’Extase by Scribian. Desha started dancing and one pose intrigued me. I carried it out and called the finished bronze Extase after the music. (1)

Reference photo of Desha Delteil for The Vine

After Desha became Frishmuth’s main model and inspiration, her work took on a new life and began to show originality that it had previously lacked. Using Desha as her muse, Frishmuth’s pieces were injected with life and movement as Desha brought out some form of organic inspiration within Frishmuth. The finished pieces reflect a shared connection between the two women that goes deeper than merely an artist and her model. With Desha as her most influential muse, Frishmuth would solidify her place as one of the most celebrated American female sculptors of the early twentieth century.

Diana (The Hunt), Harriet Whitney Frishmuth and Karl IIlava, 1921, Bronze, McClung Museum, Bequest of Frederick T. Bonham, 1958.5.115

The Star, Harriet Whitney Frishmuth, 1918, Bronze, McClung Museum, Bequest of Frederick T. Bonham, 1958.5.119

The Vine, Harriet Whitney Frishmuth, 1923, Bronze, McClung Museum, Bequest of Frederick T. Bonham, 1958.5.314

Reading Between the Lines: Hidden Histories

The sculptures that Frishmuth would produce with Desha as her main muse used dance and the nude female form in beautiful ways that resonated deeply with the art world and the public. In sculptures like both Extase and The Vine, Desha is “absorbed in physical ecstasy” and “expressing powerful and triumphant sexuality” (2).

Art historians have widely presumed that Frishmuth was a lesbian, although she never discussed her sexuality publicly. The nudity featured in her sculptures is “undeniably sensual” but lacks overt eroticism (3). Reflecting on the interview featured above, one might deduce that Frishmuth and Desha’s relationship was more intimate than that of an artist and model. Frishmuth seemed to have a fascination with Desha that went beyond art, and although Desha would marry a man in 1930, she posed for Frishmuth through 1930 until she moved with her husband to France, where she maintained contact with Frishmuth for the rest of their lives.

In 1947, Frishmuth met Ruth Talcott through a mutual friend. Ruth became Frishmuth’s secretary, bookkeeper, and eventually her “life companion.” The use of this term throughout records and accounts of Frishmuth and other historical figures’ lives implies ambiguity about Ruth and Frishmuth’s relationship. However, given other evidence and subtext within archival documents and accounts, this term can be coded as referring to romantic or sexual relationships. In 1951, Frishmuth and Ruth bought a house together in Connecticut, and roughly ten years later, Frishmuth deeded part of the property to Ruth. In 1967 they moved into another home and spent the remainder of their lives together until Frishmuth’s death in 1980. During their time together, Frishmuth still maintained close ties to Desha. The two continued to visit one another as Frishmuth would travel to Paris and Desha to the U.S. In 1980, Desha died only seven months after Frishmuth.

By digging deeper into Harriet Whitney Frishmuth’s life and her relationships, we can infer that, while not explicit, her LGBTQ+ identity and sexuality as a woman and an artist heavily influenced her work. The repression she may have faced publicly by not being able to be “out” was channeled into liberatory and celebratory art of women. By bringing these “hidden histories” to light, we can celebrate the artistry of Frishmuth fully and continue to highlight her and other LGBTQ+ artists within the museum space.

The McClung is committed to telling these stories and aims to be a safe space for learning, exploring, understanding, and living LGBTQ+ experiences for our campus and the broader community. We hope that by highlighting pieces in our collection, like these sculptures by Frishmuth, and by telling her story and the stories of others like her, we may begin to undo the erasure of LGBTQ+ narratives from museums.

(1) Quoted in Dreiss 1994

(2) Dreiss 1994

(3) Conner, Hohmann, Rosenblatt, and Tolles 2006

Additional Reading:

- Dreiss, Joseph G., “The Sculpture of Harriet Whitney Frishmuth and New York Dance.” The Courier, 312 (1994): 29-40.

https://surface.syr.edu/libassoc/312 - Proske, Beatrice G., “Harriet Whitney Frishmuth: Lyric Sculptor.” Aristos: The Journal of Esthetics 2, no. 5.(1984): 1-5. https://www.aristos.org/backissu/frishmuth.pdf

- Conner, Janis, Frank Hohmann, Leah Rosenblatt Lembreck, Thayer Tolles, Captured Motion: The Sculpture of Harriet Whitney Frishmuth, A Catalogue of Works, New York, (2006).

- Special Collections Research Center, Syracuse University Library, Syracuse, N.Y. https://library.syracuse.edu/digital/guides/f/frishmuth_hw.htm