“American Chestnut” by Kerry Wixted, CC BY-NC 2.0.

When you hear “chestnuts” your first thought may be of Nat “King” Cole’s famous holiday song and “roasting on an open fire”, but did you know that right now is actually the peak time for chestnut harvesting? Most nuts are fall staples for harvesting and storing, especially for later colder months when there are fewer viable food sources. Unfortunately, chestnut harvesting mostly ceased in the early 1900’s when the blight fungus, Cryphonectria parasitica, wiped out the majority of the American Chestnut (Castanea dentata) trees in North America. Any chestnuts you see today in grocery stores around holiday season have most likely been imported. Today, the USDA considers the American Chestnuts to be “functionally extinct.”

Characteristics:

“American Chestnut flowering structure 5” by Bob MacInnes, CC BY 2.0.

The American Chestnut (Castanea dentata) belongs to the Beech plant family, Fagaceae, and can grow up to 35 feet in its first twenty years and upwards of 115 feet at full maturity. This deciduous tree is mostly found in the wooded areas of the Appalachian Mountains and foothills, particularly in sunny areas where overstory trees have been removed or at the edges of the forest and along roadsides. Chestnut trees flower in early summer and produce either only male flowers or both male and female flowers, but rarely self-pollinate. The male flowers are white catkins, seen in the image below, which are also quite odorous. The female flowers are small burs that contain up to three nuts at maturity. When both female and male flowers are present the catkins are considered to be bisexual. In the fall, the long, toothy leaves turn yellow, and the burs open, releasing the nuts for harvest.

Historical Uses:

Especially among the Cherokees, chestnuts had a wide variety of uses as medicine, food, dye, lumber, fence rails, and firewood. Medicinal uses primarily targeted the leaves and bark. Teas were made from the leaves to remedy typhoid and stomach pains. Year-old leaves were specifically used to make tea for heart trouble, while leaves of young sprouts were used to cure old sores by dipping in hot water and applying. To make a cough syrup, leaves were boiled with mullein and brown sugar. Additionally, cold bark tea with buckeye was used to stop bleeding after birth. Chestnut bark was also used in the production of brown dye. Galls, abnormal outgrowths on the tree, were warmed and used to recede an infant’s navel. As food, chestnuts were used by the Cherokees as a coffee substitute; ground into meal to make bread; and also boiled, pounded into corn, kneaded, wrapped in a green corn blade, boiled again and eaten.

The Iroquois also made use of chestnuts and their parts as medicine and food, as well as insecticide. They made compounds for dermatological aid including a wash to relieve “Italian Itch” and a wood powder that remedied chafed infants. The oil from nutmeat was also used alone or mixed with bear grease on the hair (this combination was also utilized for an insecticide against mosquitos). The Iroquois also used chestnut medicinally for dogs by mixing the bark into a young dog’s food to help against worms. They cooked numerous foods with chestnuts including beverages, breads and cakes, pies and puddings, sauces, soups, and used it as flavor additives to other foods. This was achieved primarily by means of crushing the nuts, often forming it into a flour and/or boiling to extract the oil.

“American Chestnut” burs, by Rachid H, CC BY-NC 2.0.

The Mohegans too, used chestnut for medicinal purposes. This included using an infusion of the leaves for rheumatism, colds, and whooping cough.

When Europeans began settling in the Appalachian Mountains, they widely used chestnut as food, lumber, and livestock feed. Chestnuts were a reliable food source for the regional wildlife, which also assisted with game hunting. Given its resistance to rot, chestnut was the foundation of choice for log cabins. In Bethany Baxter’s (2009) “Oral History of the Chestnut in Southern Appalachia”, the interviewees recounted how entwined chestnuts and the practice of harvesting and gathering them was in Appalachian lifeways before the blight. From a snack in the woods, to a survival food when there was no other food or means to acquire any, to a community gathering of collecting for holiday meals or trading for other goods, it is evident that the Chestnut was abundant and cherished.

Archaeology of Chestnuts:

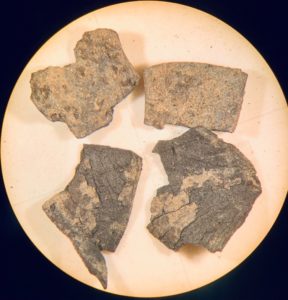

Archaeologically, especially in the southeastern United States, we do not see the remains of leaves, which are too fragile to be preserved when exposed to fire, as the primary means of plant preservation in our region is through carbonization. However, the wood, bark, and sometimes nutshells and nutmeats are found carbonized since they are more robust. The nutshells are also inedible by-products that were tossed aside and left behind when processed. In the image of “Chestnut Shell” below you can see the microscopic view of pieces of chestnut shell recovered from the archaeological site 40LD17 in Loudon County, Tennessee. “Chestnut Meat” displays the microscopic view of chestnut meats well preserved alongside the nutshell. For size reference, “Chestnut Meat and Shell Fragments” shows a side-by-side comparison of the recovered nutshell and nutmeat (with a paintbrush pointing to the nutmeat) outside of the microscope.

“Chestnut Shell” from 40LD17 under the microscope. Courtesy of Kelly Santana.

“Chestnut Meat” from 40LD17 under the microscope. Courtesy of Kelly Santana.

“Chestnut Meat and Shell Fragments” from 40LD17 outside of the microscope. Courtesy of Kelly Santana.

Restoration Efforts:

With a plethora of uses that supported lifeways for thousands of years, you may ask yourself, is there any hope for restoration of the American Chestnut? The answer is a hopeful yes. Researchers are currently locating, pollinating, and harvesting nuts from native American Chestnut trees to work towards breeding a blight-resistant American Chestnut that can be restored. Many small stump sprouts of the American Chestnut still exist on the floor of the forest and are able to grow in sunlight up to 20-30 feet and flower, but then are taken over by the blight. Use of the Chinese Chestnut, which is blight-resistant, for cross-pollination and breeding is being studied. The American Chestnut Foundation (TACF) uses volunteers to help locate these small stump sprouts to use for research. More information can be found on the TACF website on how to submit any chestnut findings in your region.

The Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians’ National Resource Department (EBCI NRD) is currently working with TACF to research how to bring the beloved plant back into the local ecosystem within the Qualla Boundary in western North Carolina. This includes planting of developed blight-resistant chestnut seeds, locating native American Chestnut stumps that could be used in cross-pollination, and compiling information on how chestnut was used by ancestors in the past to share with the EBCI community, so that they may then be used again.

If any information is known on locations of American Chestnut within the Qualla Boundary or of other traditional uses, please reach out to the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians’ National Resource Department, who are collecting information for forest management and cultural preservation within the tribe. With a little help from the community, hopefully we can see these giants begin to rise again!

For More Information:

Baxter, Bethany N. 2009. An Oral History of the American Chestnut in Southern Appalachia. Master’s thesis, University of Tennessee, Chattanooga.

Hamel, Paul B., and Mary U. Chiltoskey. 1975. Cherokee Plants and Their Uses – A 400 Year History. Herald Publishing, Sylva, North Carolina.

Moerman, Daniel E. 1998. Native American Ethnobotany. Timber Press, Portland, Oregon.

Perry, Myra Jean. 1975. Food Use of the “Wild” Plants by Cherokee Indians. Master’s thesis, University of Tennessee, Knoxville.

The American Chestnut Foundation (TACF). 2021. Electronic document, http://acf.org.

US Department of Agriculture, Natural Resources Conservation Service. 2021. PLANTS Database. Electronic document, https://plants.usda.gov/home.

Van Leuven, Jaime. 2021. “Initial Phase of American Chestnut Restoration Has Begun.” Cherokee One Feather. Electronic document, https://theonefeather.com/2021/07/15/initial-phase-of-american-chestnut-restoration-has-begun/.