December: Mistletoe (Phoradendron leucarpum)

Oak Mistletoe, Phoradendron leucarpum

Mistletoe (or specifically Oak Mistletoe [Phoradendron leucarpum]) is our festive holiday plant of the month for December. This evergreen plant with white berries is a popular decorative item in homes over the holidays.

American mistletoe fruit and flowers, Laurens County, Georgia. Photo courtesy of Alan Cressler, USGS.

Fun fact: Mistletoe is commonly confused with holly (Ilex sp.), a similar plant with evergreen leaves and berries, although the berries are commonly red. Mistletoe species native to Europe often have red berries rather than white, which adds to the confusion with holly.

Christmas Holly/Bettina darveaux, Photo courtesy of William S. Justice, USDA, NRCS. 2020. The PLANTS Database (11 December 2020). National Plant Data Team, Greensboro, NC 27401-4901 USA.

Unlike holly, mistletoe is a parasitic plant. It grows in a shrub-like shape, usually in the highest parts of the host tree in order to receive full sun. It draws water, minerals, and nutrients from the host tree through its roots. Mistletoe also produces its own energy and sugars through photosynthesis in its leaves.

Oak mistletoe is classified in the Sandalwood Family (Viscaceae). This plant and other members of the Phoradendron genus grow throughout Tennessee and eastern North America. Characteristics of oak mistletoe include simple leathery leaves opposite in arrangement from each other. The flowers lack showy and vibrant petals compared to typical plants that rely on pollinators for survival. The Phoradendron genus is identifiable based on the following plant characteristics:

- A single plant contains multiple flowers but each flower only contains male or female parts.

- Female flowers in later stages of summer produce white flowers, which later form into pea-sized white, pink, or red berries over the winter.

- Parasitic nature primarily affecting deciduous trees, growing attached to the tops of the tree’s highest limbs to allow for more effective photosynthesis through its leaves.

Female silky flycatchers feed on mistletoe berries in the winter. Photo by Todd Esque, USGS Western Ecological Research Center. Public domain.

A Mistletoe bird munching on its favorite meal of mistletoe fruit. Photo: James Peake/Alamy

Mistletoe is a perennial plant, and reproduces itself through seeds. Mistletoe not only relies on the host tree for survival, then, but also birds for seed dispersal. The plant is toxic to humans when consumed, but it provides staple nutrients to birds throughout the winter season. The pulp of the berry is sticky, allowing the seeds to adhere to birds as they feed. The seeds are then deposited on surrounding branches and eventually germinate in the spring depending on the moisture conditions of the environment. Many birds eat mistletoe berries as a staple resource during the winter months, including the female silky flycatchers, mistletoe birds, grouse, mourning doves, bluebirds, evening grosbeaks, robins, and pigeons (Puckett and Esque 2016).

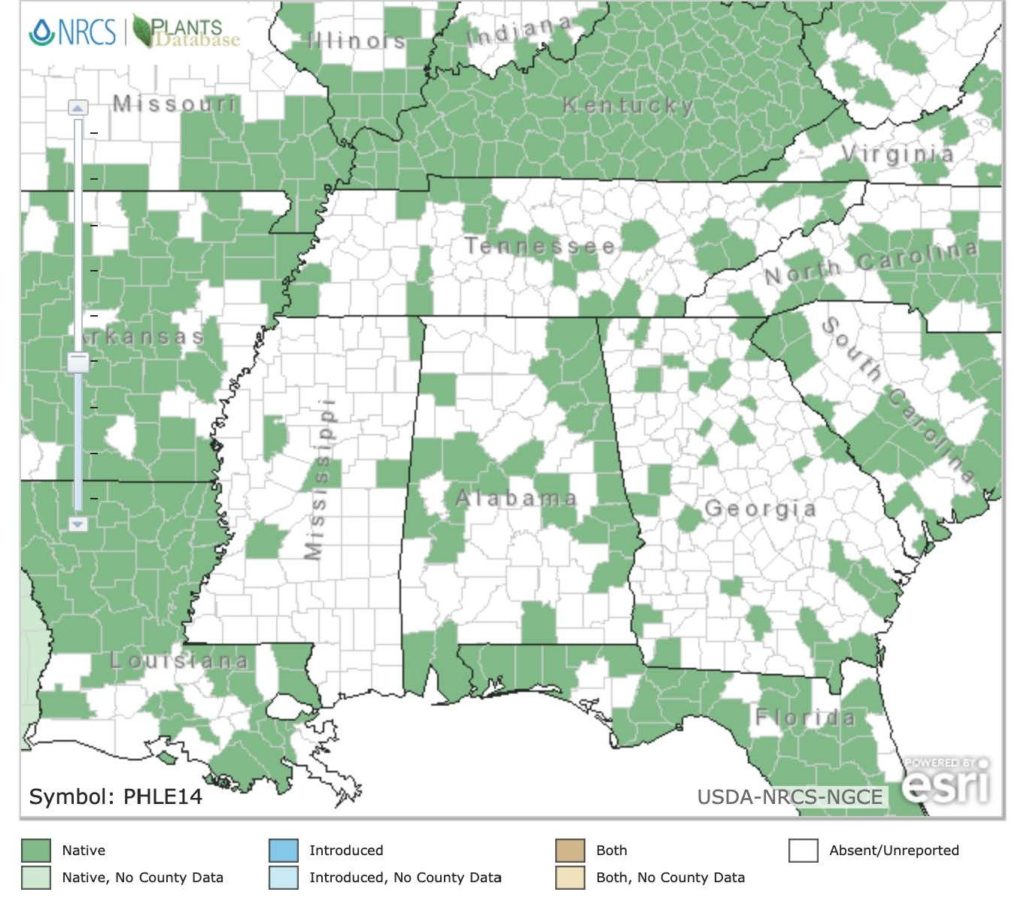

Map from USDA Natural Resources Conservation Services for Oak Mistletoe plants, 2020, Map courtesy of USDA.

Mistletoe has an interesting history of uses. In the New World, Native American groups used mistletoe for a variety of medicinal purposes. The Cherokees used mistletoe, usually in the form of infusions, to treat a variety of conditions. These include high blood pressure, epilepsy, “fits”, headaches, as a “medicine for pregnant women”, and to treat “love sickness.” The Creek Indians used the leaves and branches to treat “lung troubles” and tuberculosis. The Seminoles rubbed a decoction made from the leaves onto sore limbs and joints as an anti-rheumatic treatment. More generally, they used mistletoe as an emetic in religious ceremonies, and also to treat “chronically ill babies.” Similarly, the Houma Indians of Louisiana used a decoction of mistletoe as a general panacea for weakness and debilitation (Moerman 2004).

In the Old World, Norse mythology includes the story of Balder, son of Frigg (goddess of love and beauty), who is killed by an arrow made of mistletoe. In some versions of the story, Frigg tries to bring her son back to life, promising kisses to those gods who aid her. Other versions claim that her tears are represented by the pearly berries of mistletoe. Ultimately, the gods decreed that mistletoe would cause no further harm but instead bestow happiness. This myth is the foundation for the holiday tradition of kissing under mistletoe. Washington Irving wrote about this tradition in the 1800s: “Young men have the privilege of kissing the girls under [mistletoe], plucking each time a berry from the bush. When the berries are all plucked the privilege ceases” (Dunn 2011).

Druid traditions establish the placement of Mistletoe over entryways or door frames. Old Druid priests would perform a midwinter ceremony to bless boughs of Mistletoe, which were then distributed to families to hang above the doorways to ensure safety and to repel bad luck for the household (Dunn 2011).

Oak Mistletoe in Edmond, Oklahoma 2020. Photo courtesy of Peggy Humes.

Oak Mistletoe in Edmond, Oklahoma 2020. Photo courtesy of Peggy Humes.

Our Graduate Research Assistant, Peggy Humes, learned about mistletoe while in grade school in Oklahoma. Mistletoe was the state flower of Oklahoma, even though it lacks true flowering blossoms, until 1986, when it was replaced with Indian blanket (Gaillardia pulchella)–but that’s a story for another month!

For more information on Mistletoe (Phoradendron spp.) and Oak Mistletoe (Phoradendron leucarpum), check out the following resources.

Online:

“Mistletoe: The Evolution of a Christmas Tradition.” 2011. Rob Dunn. Smithsonian Magazine.

“Mistletoe”. 2020. Weed Science Society of America.

“Not Just for Kissing: Mistletoe and Birds, Bees, and Other Beasts.” 2016. Catherine Puckett and Todd Esque. US Geological Survey.

“Phoradendron leucarpum.” 2018. Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center, University of Texas at Austin.

“Phoradendron leucarpum.” 2004. Daniel Moerman. Native American Ethnobotany: A Database of Foods, Drugs, Dyes and Fibers of Native American Peoples, Derived from Plants.

“Phoradendron leucarpum.” 2020. Plants Database, USDA Natural Resources Conservation Services.

“Plant of the Week: Mistletoe.” 2020. Gerald Klingaman. University of Arkansas Division of Agriculture Extension Research and Horticulture:

Missouri Botanical Gardens, Plant Finder.

University of Tennessee Herbarium.

Books:

Barlow, B. A. “Biogeography of Loranthaceae and Vise,” The Biology of Mistletoes, D. M Calder and P. Bemhardt, eds. Academic Press Inc., NY.

Edge, John T. (Ed.), 2007. The New Encyclopedia of Southern Culture: Volume 7: Foodways. University of North Carolina Press. Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

Elpel, Thomas J., 2018. Botany in a Day: The Patterns Method of Plant Identification 6th ed. HOPS Press, LLC. Pony, Montana.

Fernald, Merritt, and Alfred Kinsey, 1943. Edible Wild Plants of Eastern North America. Harper & Row Publishers Inc. New York City, New York.

Hawksworth, F. G. “Crop loss assessment.” Proc. E. C. Stakman Commemorative Symp. Univ. Wmn. Exp. Stn. Misc. Publ. 7.

Jepson, W. L. A Manual of the Flowering Plants of California. Univ. of California Press, Berkeley.