The following essay was originally published in Volume 6, Issue 1 (2015) of Pursuit: The Journal of Undergraduate Research at the University of Tennessee.

by Christine Dano Johnson, Student Assistant, McClung Museum, The University of Tennessee, Knoxville

Advisor: Mark Hulsether

Not Just Objects: Alaska Native Material Culture

For two years I called Alaska home. Prior to living so far north I held a few common misconceptions about Alaska Natives and their material culture, and the stereotypical “Eskimo” image complete with harpoon and fur-lined parka came to mind often, as did the frozen tundra and twenty-four hours of darkness in winter. Alaska does have plenty of tundra, and plenty of darkness in winter, but that is not the whole story. While living an hour north of Anchorage, in a village that sat in a birch and fr forest surrounded by glaciers and bald eagles, I learned that the people of Alaska are even more diverse than the environment.

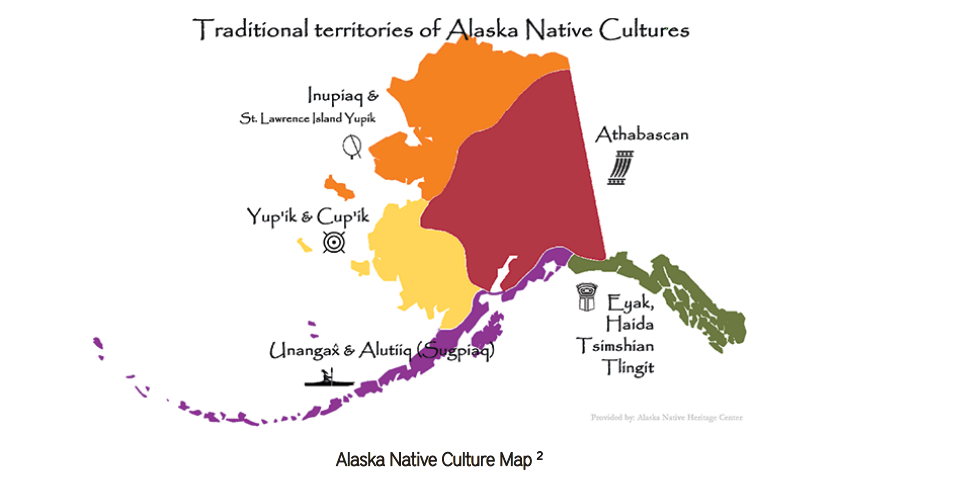

Upon my return to the south, where I now work a curatorial intern at the McClung Museum of Natural History and Culture at the University of Tennessee, I found myself surrounded by Alaska’s history and culture again in the form of over one hundred Alaskan Native objects of material culture in the museum’s collections. These objects range in geographic and cultural diversity from the far north of the state to three thousand miles away on the southeastern peninsula. When I began working with the objects I noticed that regardless of whether it originated from Tikigaq in the north or Wrangell in the south, objects were labeled with generic terms such as “Alaskan Eskimo” or “Alaska Indian.” Whether the object is a kuspuk (tunic dress) made by an Iñupiat woman in Kotzebue in the north or a two hundred year old nax’w (halibut fishing hooks) made by a Tlingit fisherman in Wrangell to the south, generic terms identified their origin. Alaska, according to the Alaska Native Heritage Center in Anchorage, is home to “eleven distinct cultures, speaking eleven different language and twenty-two different dialects.”1 The vague descriptions at the McClung Museum are representative of a larger problem in museums. Through the lens of these one hundred and twenty-four objects, I concluded that the long-standing curatorial practice of giving broad and erroneous labels to material culture of Indigenous origin is a direct effect of colonialism. It succeeds in perpetuating the pain inflicted on the Indigenous communities from which the objects originate. Going forward, museums like the McClung with Indigenous material culture in their stewardship must adopt collaborative methods with source communities if they are to contribute to repairing the larger problem of colonialism.

“Degenerate” Roots

At least some of the roots of this practice can be traced to the Old World and Georges Louis LeClerc, Comte de Buffon, a 18th century French naturalist and director of the gardens at the French Museum of Natural History. His thirty-six volumes on Natural History, the Histoire Naturelle, have influenced the field of Natural History since their publication in the mid to late 1700s.3 Through his work, Buffon formulated the “degeneracy theory” about the indigenous flora, fauna, and people of the New World. He believed that the “Indians” were “cold, lazy, without feeling, stupid, and lacking in sexual drive.”4 Since they had, in his words, “failed to conquer nature,” Indians were somehow lesser than their conquerors from the Old World. The response from the “New Americans” to Buffon’s degeneracy theory was swift: Jefferson, living in Paris at the time of Buffon’s claims of degeneracy, responded to Buffon’s claims by ordering a giant moose sent over to Paris from the New World to prove America’s strength and girth.5 Jefferson did not respond to Buffon’s claims that the Indigenous population of America were “cold and lazy,” perhaps because he, like Buffon, thought them “barbarous,” as he noted in his Notes on the State of Virginia.6Charles Willson Peale, another early American (and Jefferson’s portrait painter) created the new nation’s frst museum in Philadelphia in direct response to Buffon; he rejected his degeneracy theory but applauded his museum work. In 1801 Peale created a showcase for the diversity of life in the New World, filling it with all manner of fora and fauna.7 The museum, which started as a showcase of Peale’s “Cabinet of Curiosities,” included objects and scientific studies originating from Indigenous material collected during the Lewis and Clark exhibition. Rather than refute the “degeneracy” of the Native people, the objects were classified scientifically, in the “Animal” group of “Animal, Vegetable, Mineral.”8 Since Peale’s museum served as a basis for museums in the United States, especially those dealing with Indigenous cultural objects such as Natural History museums, its legacy illustrates just how deeply rooted this complicated relationship goes back between museums and Indigenous communities.

A Painful Relationship

Two hundred and thirteen years after Peale created his Natural History Museum, museums are still often difficult places for Indigenous communities. According to Amy Lonetree, a Ho-Chunk professor of American Studies specializing in museums, “museums can be very painful sites for Native peoples, as they are intimately tied to the colonization process.”9 Using Peale’s museum and other historical institutions such as the Smithsonian Museum of Natural History and the American Natural History Museum as models, American museums historically displayed Indigenous artifacts as curiosities, as a complement to fora, fauna, and other natural history, or in displays featuring the way they lived in the past, arranged around a museum’s archaeological holdings associated with the Indigenous culture. This representation of Indigenous people squarely situated in the past or as “natural histories” relegates them to a “primitive” past, which, according to Susan Sleeper Smith, influenced what museums collected and displayed.10

This is not to say that archaeological, historical or cultural objects are irrelevant and should not be displayed in museums that serve a broad public, but we must acknowledge the mixed feelings and painful memories of the colonization process on the communities from which these objects originated. W. Richard West, Cheyenne and founding director of the National Museum of the American Indian, states that “There was…this historic love/hate relationship between museums and Native communities. We…value them…because they have our stuff, and we hate them because they have our stuff.”11 Museum practices of relegating Indigenous cultures to primitive pasts do nothing to serve the communities from which their objects originate; they exist only to narrate a story about the successes of colonialism for what museum studies scholar Laura Peers calls “dominant society audiences.”12 To change their relationship with Indigenous communities and to better interpret their material culture, many museums are moving forward via collaboration with Indigenous communities, which according to Lonetree, “is becoming more the norm than the exception.”13 This practice should be the norm rather than the exception not only in the care and display of Indigenous objects but in the research and naming of culture groups represented in museums and their material culture, as in the case of the McClung Museum. If museums are to be the stewards of much of this “stuff,” as West refers to Indigenous material culture, they must eradicate the use of vague and overly broad terms. These practices erroneously indicate that indigenous people are a collective, homogenous group that can be swept into that extinct past when, according to Cherokee writer Thomas King, “there never was a collective to begin with.”14

The Problem with “Eskimo”

In his essay Indian, Robert Warrior states that the term, “Indian” is “monolithic and helps bolster the mis-impression that all indigenous people are the same.”15 Among the most visible of the effects of this mis-impression are in the museum setting, in both the identifying of objects of indigenous material culture and in how these objects are interpreted for the general public. In working with Alaska Native material culture, the term “Eskimo,” like “Indian,” also bolsters this idea of sameness. “Eskimo” is thought to have derived from an Ojibwa term meaning “to net snowshoes.”16 Among the indigenous people of northern Canada, who prefer the term “Inuit,” and the indigenous people of Greenland, who prefer “Greenlanders,” it is considered highly derogatory. In Alaska, it is not seen as overly derogatory, but the word only refers to the Iñupiat, Aleut, and Yup’ik people. Incidentally, these people do not consider themselves “Indian,” as is the case with the Athabaskan, Tlingit, Eyak, and other communities that historically and presently inhabit other areas in Alaska. However, for the purposes of an institution that is steward to Indigenous material culture and also serves the purpose of scholarship, the term “Eskimo” is extremely problematic, simply because it does not give enough detail.

Robert Warrior points out that the term “Indian” (or “Eskimo) does not take into consideration that the most accepted practice among Alaska Natives, and other North American Indigenous people is “to use the names specific tribal groups have for themselves (Dine, Dakota, Yup’ik, Ojibwa, or Yakama).”17 Further, in the case of the objects at the McClung Museum and other similar museums, some objects are labeled as being “Eskimo” or “Indian” when they are neither. A carving featuring an Alaska Native totem pole collected in southeastern Alaska cannot by definition be “Eskimo” and conversely, a wooden mask used for storytelling and dancing that originated from the Iñupiat village of Kivalina cannot by definition be “Indian.” The McClung Museum’s original classification of each of those objects read in exactly that incorrect and vague manner.18 The reasons vague classification have continued into the twenty-first century are vast, and have as much to do with stretched resources pertaining to research and collections care as they do with ignorance or an adherence to colonial attitudes. Museums According to Robert Warrior, museums must“rethink their understanding of the continent” and confront ignorance.19 A university museum focusing on culture must carefully analyze such generalities and eradicate them. Through collaboration with community members, these omissions and mistakes can be ratified, bringing integrity to the museum collection and facilitating the healing of past museum wrongdoings.

Objects as Living Entities: The Problem of “Culturally Unidentifiable” and

NAGPRA

The vague identifications and descriptions in the McClung Museum’s Alaska Native collections harken back to colonial museum practices, simply due to the fact that many of the objects have not been researched since they were originally accessioned in the early 1950’s. Many of the objects are labeled with problematic, generic identifiers such as “Eskimo” or “Indian,” as mentioned in the previous section. However, some simply bear the area from which they were purchased or acquired; other objects, featuring the term “Culture Group Unknown,” have no vague identifier or region at all. There are several problems with this term. According to Trudy Nicks, senior curator at the Royal Ontario Museum, many Indigenous communities “see objects as living entities.”20 Rosita Worl, President of Sealaska Heritage, which represents Tlingit, Tsimshian, and Haida communities in Southeastern Alaska, confirms this by stating, “These are not just material objects […] they are associated with our ancestors.”21 To apply a vague term such as “Indian” or “Eskimo”, mislabel with an incorrect culture, or call an object’s culture group unknown or unidentifiable is to mistreat both the object and the people associated with it, a practice that harkens back to colonialist practices that ranged from ambivalence to outright persecution. When Joseph Sowmick, former tribal spokesman of the Saginaw Chippewa in what is now Michigan, learned that some of the remains of his ancestors and associated funerary material culture had been labeled “Culturally Unidentifiable” by the University of Michigan museum staff, he spoke out: “Culturally Unidentifiable? We undeniably say no to this miscategorization and are extremely offended by it.”22 By calling the Saginaw remains “unidentifiable,” the museum took away the community’s power to self identify or affirm its own historical and current existence. Further, since most Indigenous communities feel that objects created by their ancestors are to be treated as if they were living entities – with respect and reverence and given the proper name – the label renders even human remains as mere “objects.” In order to achieve any level of respect, members from source communities must be involved in the research, representation and care of their historical artifacts.

In December of 2013, a group of curators at a cultural museum in Springfield, Massachusetts began pulling objects in their collections purported to be from Alaska for a planned exhibition on Alaska Native culture. One object they found was labeled simply as “An Aleutian Mask.” The description, and the object, had not been researched or touched from the time of its donation more than one hundred years prior.23 One of the curatorial staff, an anthropologist who was familiar with Alaska Native communities, questioned the veracity of the assumption that the mask was Aleutian or was even a mask at all, and confirmed with the Alaska State Museum and the Sealaska Heritage Association (a cross-cultural group of Tlingit, Haida, and Tsimshian artists and elders) that the mask was instead an extremely rare Tlingit war helmet. According to Rosita Worl, the helmet, “embodies the spirit of our ancestors […] and its emergence signifies that the ancestral spirits want and need to come home.”24

Museums also engage in collaborative efforts with source communities through the auspices of NAGPRA, or the Native American Graves and Repatriation Act. NAGPRA, a federal law passed in 1990, provides a process for museums and Federal agencies to return certain Native American cultural items, such as the Tlingit war helmet, back their source communities. The act protects human remains, funerary objects, sacred objects, and objects of cultural patrimony and its jurisdiction works to return the objects to “lineal descendants, and culturally affiliated Indian tribes and Native Hawaiian organizations.”26 One important effect of the process of removing either vague or incorrect identifiers is the reintroduction of Indigenous communities to their ancestral objects, possessions lost via the looting of their villages by explorers and the American military as recently as the early twentieth century. These artifacts, in many cases, are repatriated back to the communities from which they originate, creating a powerful form of closure and retribution for healing some of the pain of colonialism. Researching objects that have been vaguely identified with broad terms or misidentified, and working with source communities in the process, is again, just the beginning of this healing process that means more to Indigenous communities than having objects returned.

Two Successful Models of Community Collaboration

Since the standard practices in museum collection and exhibition in regards to Indigenous material culture has roots that reach far back and into the United States’ largest and most prestigious cultural institutions, it makes sense to begin the collaborative approach at these institutions to reassess, research and identify the objects. One institution that has successfully used a model of community collaboration is the Smithsonian Institution’s Arctic Studies Center in Anchorage, Alaska. In 2010, the center completed a massive renovation by restructuring how it researched and displayed the over 30,000 (mostly collected between the mid-1800s and the mid-1900s) Alaska Native objects that were stored in the National Museum of the American Indian and the National Museum of Natural History.27 They call the project Sharing Knowledge, and the goal is to share the rich history and culture with current and future generations of the source communities that the collection represents. Through the use of conversations and investigations between curators, heritage organization representatives, and elders surrounding the origins, terminology, and use of each object, what was once a scattered collection of vaguely “Eskimo” or “Alaskan” artifacts now tell the narrative of the people from which each object originates. In the museum space, the objects are displayed in a manner which was approved by a consensus of the source cultures’ representatives. On the museum collection’s website, the conversations are included in the accession, accessible for digital visitors, and the names for each object is prominently displayed in the language from which they originate. In one example, a Saint Lawrence Island Yup’ik seal gut

parka is discussed with elders from the community, both in English and in Yup’ik:

“Enkaam wetku aatelleghqii anuqa kaatestaaghanghagu aqlaghami.

(Then they would put them on when wind picked up, in cold weather.)

Aasimaqegkangit qaspeghaaluki, oayughllak anuqem supugnaanghilkangi.

(They put them on over other clothing, because wind won’t blow through.)”28

The digital and physical exhibition have allowed visitors from source communities living in and out of Alaska to see the material culture of their ancestors up close. During its opening, an Alutiiq teenager was able to investigate the masks his ancestors made, which helped him paint the ones his father carved. Another visitor who comes from an Iñupiat community was able to see a pair of ivory snow goggles just like the pair her grandfather made for her when she was a child.29

Another successful model of collaboration occurred in 1994 at the Etnologisches Museum in Berlin. Like the collection at the Smithsonian Institution and the McClung Museum, the objects ranged in geographic and cultural diversity; most had been placed into a single comprehensive “Eskimo” category.30 One of the highlights of the collection was a group of Yup’ik masks, which exhibited in Anchorage in 1996, prompting a desire from elder members of the Yup’ik community to take a look at the material culture of their ancestors that were being held in a museum over four thousand, five hundred miles away. A rich conversation into Yup’ik culture resulted; the elders were able to enrich the museum with knowledge and insight into its holdings, and the elders were able to take tangible evidence of the objects of their ancestors back to their communities. One elder illustrated the grief surrounding the effects of colonialism on his community, and how the collaborative process allowed some healing to being.

“Many of us seem to have been in the dark for many years. […] Now that the knowledge is out, I hope our work together will be written and presented to our people. […] If our people begin to see them and understand the culture of our ancestry, they might begin to believe and gain pride in their own identity. […] My hope is that our work will bring our people closer to their own culture.”31

Thorough research and collaboration with source communities are not only an argument for academic accuracy – they are a means to begin healing the wrongs of colonialism. Museums, through collaborative efforts, can assist in facilitating steps towards this healing.

Efforts to Remedy the Alaska Material Culture at the McClung Museum

In researching the McClung Museum’s one hundred and twenty four Alaska Native objects, I have adopted the collaborative approaches illustrated in the previous section. The museum will exhibit one object, a fishing hook carved in the shape of a halibut, beginning in January 2015. Since we knew the hook was collected in Wrangell, Alaska by Presbyterian missionaries, I ascertained that it was of either Haida, Tsimshian, or Tlingit origin. To confirm its origins, use, possible age, and affiliated community, I contacted Sealaska Heritage, who represents artists and elders from each of those culture groups. After examining photographs of the hook, Donald Gregory, the Tlingit artist in residence at Sealaska, informed me that the hook is of Tlingit origin, and provided a wealth of information about the construction, use, and traditional fishing practices of the Tlingit. According to Donald, “Tlingits believe our hooks have a spirit and when you fished them it was common to talk to your hook and say nice things to it to prepare it for successful fishing. The fisherman that fished this hook must have said a lot of nice things to it.”32 Thanks to the adoption of a collaborative approach, not only did the museum learn more about the object and are now able to give it a culture group, we also have the ability to label it with its Tlingit name: nax’w.

“Tlingits believe our hooks have a spirit and when you fished them it was common to talk to your hook and say nice things to it to prepare it for successful fishing. The fisherman that fished this hook must have said a lot of nice things to it.” Donald Gregory, Tlingit artist.

Because of the accession record, we knew the nax’w originated from Juneau. In working with another object that has no geographic or collection history, the execution of a collaborative effort has included a few extra steps but has proven no less impactful. One of the one hundred and twenty four Alaska Native objects is a small wooden mask with faint lines of red and black paint and tattoo lines carved on each side of the nose. Labeled “Eskimo/Inuit” with no geographic location given as to its procurement, I began the process from scratch, inspecting and noting all the mask’s details and consulted the databases at the Smithsonian Arctic Studies Center. Based on the mask’s features, I guessed that it might come from a northern community, and searched other museums in Alaska for either Iñupiat or Yup’ik masks. I eventually stumbled upon a photograph of a contemporary Iñupiaq mask carver named Art Oomittuk holding a mask almost identical to the one held by the McClung Museum. His ancestors made masks like the one at McClung, in the small community of Tikigaq, which lies on the Bering Sea. In his artist statement, Art says:

“My Ancestors occupy what we call the Arctic and have lived there for centuries… More specifically, I am from Western Alaska, the village of Tikigaq, I am Tikigaqmuit (Ungasiksikaaq, Qagmaqtuuq)… My name is Anaqulutuq, Othniel Art Oomittuk Jr… Identity!!!”33

I contacted Art via his website, and he plans to visit the museum in the near future to inspect the mask, but confirmed that the mask does appear to be from his home village of Tikigaq. Sharing knowledge with Art and Donald Gregory on the nax’w, not only enriches the curatorial research of the object, but also addresses the need to put Indigenous communities in control of their own material culture and to identify themselves. Amy Lonetree advocates for museums to be “transparent in [their] decision making and willing to share power. New museum theory is about decolonizing, given those represented control over their own cultural heritage.”34 My hope for the outcome of the current collaboration with these communities is to be able to give proper respect to both the makers of the object and its descendants.

Conclusion: After the Research and On Exhibition

Though my research the purpose of this essay has been in relation to historical and ancestral Indigenous material culture, it is my hope that by working with contemporary artists, such as Art Oomittuk and the members of Sealaska’s Native Artists Committee, I properly affirm the contemporary existence and refute the myth that Indigenous communities exist only in the past. Museums must not only involve the communities they represent, but they must adopt other exhibition techniques if they are to, in the words of Robert Warrior, “create deeper scholarly understandings of features of contemporary Native life.”35 Through the collaborative efforts with Sealaska Heritage, our exhibit label on the nax’w looks quite different than it looked prior to reaching out to Donald Gregory. Where the old exhibition label featured a detached curatorial-authoritative voice, the new label centers the story of the hook from a Tlingit perspective:

“The Tlingit of southeastern Alaska use náx’w (wooden hooks) to help them catch halibut, an extremely large fish weighing on average 30-35 pounds, on the open sea during winter and early spring. Traditionally made náxw like this one are extremely strong and efficient at reeling in halibut, and were constructed with hard woods such as cedar, yew, or alder and feature an iron barb. According to Tlingit carver Donald Gregory, “Tlingits believe our hooks have a spirit and when you fshed them it was common to talk to your hook and say nice things to prepare it for successful fshing. The fisherman who fished this hook must have said a lot of nice things to it.”36

For too long, museums treated objects of Indigenous material culture and their source communities as what Brenda McDougal calls “relics of a colonial past without a place in a postmodern, global society,”37 In the case of the McClung Museum, the adoption of a collaborative approach has contributed to the healing process between museums and source communities, and enriched our stewardship and knowledge of these incredible pieces of Alaska Native material culture.

Endnotes

1 “Education and Programs.” Cultures of Alaska. Accessed November 26, 2014. http://www. alaskanative.net/en/main-nav/education-and-programs/cultures-of-alaska/.

2 “Education and Programs.” Cultures of Alaska. Accessed December 1, 2014. http://www. alaskanative.net/en/main-nav/education-and-programs/cultures-of-alaska/.

3 Scoville, Heather. “8 Great Men Who Infuenced Charles Darwin.” About Education. Accessed December 1, 2014. http://evolution.about.com/od/Darwin/tp/People-Who-Infuenced-CharlesDarwin.htm.

4 Dugatkin, Lee Alan. Mr. Jefferson and the Giant Moose: Natural History in Early America. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2009. 10.

5 “Thomas Jefferson Needs A Dead Moose Right Now To Defend America.” NPR. Accessed November 26, 2014. http://www.npr.org/blogs/krulwich/2014/01/15/262916045/ thomas-jefferson-needs-a-dead-moose-right-now-to-defend-america.

6 In Biolsi, Thomas. “Race Technologies.” In A Companion to the Anthropology of Politics, 404. Hoboken, New Jersey: Wiley-Blackwell, 2007.

7 Schofeld, Robert. “The Science Education of an Enlightened Entrepreneur: Charles Willson Peale and His Philadelphia Museum.” The University of Kansas American Studies Journal 30, no. 2 (1989): 23-25. Accessed November 18, 2014. https://journals.ku.edu/index.php/amerstud/article/ viewFile/2470/2429.

8 ExplorePAhistory.com. Accessed November 28, 2014. http://explorepahistory.com/ displayinteractive.php?interId=1-10-6

9 Lonetree, Amy. “Introduction.” In Decolonizing Museums: Representing Native America in National And Tribal Museums, 1. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2012.

10 Sleeper-Smith, Susan. Contesting Knowledge: Museums and Indigenous Perspectives. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2009. 11.

11 In Smith, Susan. Contesting Knowledge: Museums and Indigenous Perspectives. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2009. 81.

12 Peers, Laura L. Museums and Source Communities: A Routledge Reader. London: Routledge, 2003. Introduction.

13 Lonetree, Amy. Decolonizing Museums: Representing Native America in National And Tribal Museums,16. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2012.

14 King, Thomas. The Inconvenient Indian: A Curious Account of Native People in North America. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2013 GC:(2012?). NEEDED GC:?.

15 “Indian.” In Keywords for American Cultural Studies, edited by Bruce Burgett, by Robert Warrior. New York: New York University Press, 2007. 133.

16 “Inuit or Eskimo? | Alaska Native Language Center.” Inuit or Eskimo? | Alaska Native Language Center. Accessed November 28, 2014. http://www.uaf.edu/anlc/resources/inuit-eskimo/.

17 “Indian.” In Keywords for American Cultural Studies, edited by Bruce Burgett, by Robert Warrior. New York: New York University Press, 2007. 133.

18 Kivalina Death Mask. ca. 1900. Kivalina, AK. McClung Museum of Natural History and Culture. 2011.27.92. Carving. McClung Museum of Natural History and Culture. 1958.5.218.

19 “Indian.” In Keywords for American Cultural Studies, edited by Bruce Burgett, by Robert Warrior. New York: New York University Press, 2007. 134.

20 Lonetree, Amy. Decolonizing Museums: Representing Native America in National And Tribal Museums, 22. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2012.

21 Doogan, Sean. “Two Alaska Native Artifacts Return Home after Clandestine Auction Bid by Nonproft.” Alaska Dispatch. September 3, 2014. Accessed November 29, 2014. http://www.adn.com/ article/20140903/two-alaska-native-artifacts-return-home-after-clandestine-auction-bid-nonproft.

22 In Lonetree, Amy. Decolonizing Museums: Representing Native America in National And Tribal Museums, 163. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2012.

23 Andrews, Laurel. “Emergence of Rare Tlingit War Helmet Raises a Chorus for Homecoming.” Alaska Dispatch. January 7, 2014. Accessed November 29, 2014. http://www.adn.com/ article/20140107/emergence-rare-tlingit-war-helmet-raises-chorus-homecoming.

24 Andrews, Laurel. “Emergence of Rare Tlingit War Helmet Raises a Chorus for Homecoming.” Alaska Dispatch. January 7, 2014. Accessed November 29, 2014. http://www.adn.com/ article/20140107/emergence-rare-tlingit-war-helmet-raises-chorus-homecoming.

25 Courtesy Springfeld Science Museum. In Andrews, Laurel. “Emergence of Rare Tlingit War Helmet Raises a Chorus for Homecoming.” Alaska Dispatch. January 7, 2014. Accessed November 29, 2014. http:// www.adn.com/article/20140107/emergence-rare-tlingit-war-helmet-raises-chorus-homecoming.

26 United States. National Park Service. “National NAGPRA FAQ.” National Parks Service. Accessed November 30, 2014. http://www.nps.gov/nagpra/FAQ/INDEX.HTM#What_is_NAGPRA?

27 “Alaska Native Collections – Sharing Knowledge.” Arctic Studies. Accessed November 30, 2014. http://alaska.si.edu/about_this_project.asp. GC: no longer exists

28 “Alaska Native Collections – Sharing Knowledge.” Arctic Studies. Accessed December 1, 2014. http://alaska.si.edu/record.asp?id=218.

29 Hopkins, Kyle. “Anchorage Museum Opens Revamped Imaginarium, Arctic Studies Centers.” Alaska Dispatch. May 22, 2010. Accessed December 1, 2014. http://www.adn.com/article/20100522/ anchorage-museum-opens-revamped-imaginarium-arctic-studies-centers.

30 Fienup-Riordan, Ann. “Yup’ik Elders in Museums: Fieldwork Turned on Its Head.” In Museums and Source Communities: A Routledge Reader, 30. London: Routledge, 2003.

31 In Fienup-Riordan, Ann. “Yup’ik Elders in Museums: Fieldwork Turned on Its Head.” In Museums and Source Communities: A Routledge Reader, 38. London: Routledge, 2003.

32 Gregory, Donald and Chuck Smythe. Email Message to Christine Dano Johnson, November 11, 2014.

33 Oomittuk Jr., Othniel Art. “Othniel Art Oomittuk Jr – Anaqulutuq.” Othniel Art Oomittuk Jr – Anaqulutuq. Accessed December 1, 2014. http://www.artoomittukjr.com/.

34 Lonetree, Amy. Decolonizing Museums: Representing Native America in National And Tribal Museums, 172.

35 “Indian.” In Keywords for American Cultural Studies, edited by Bruce Burgett, by Robert Warrior. New York: New York University Press, 2007. 134.

36 Shteynberg, Catherine and Christine Dano Johnson. Email message, November 18, 2014.

37 MacDougall, Brenda, and Teresa Carlson. “West Side Stories: The Blending of Voice and Representation through a Shared Curatorial Practice.” In Contesting Knowledge: Museums and Indigenous Perspectives, 167. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2009.