This exhibition explores how Napoleon Bonaparte’s invasion of Egypt in 1798?1799 influenced the rise of Egyptomania, a craze for all things Egyptian. There had always been a prior fascination about Egypt, ever since the Greco-Roman period up through the eighteenth century and a lively interest in Orientalism. Napoleon and Egyptomania in Tennessee, curated by Elaine A. Evans, traces this interest in Egypt and focuses on the growing obsession in the wake of the Napoleon Expedition. Its resulting publications contributed to the lasting influence on design movements of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries in Europe and the United States. The McClung exhibition brings this topic close to home using images and objects that reflect Egyptian influences—all found in Tennessee.

Napoleon had not only brought his French forces to Egypt in 1798, but also a group of some 167 French scholars to record the ancient monuments and modern aspects of an exotic country. During this time the Rosetta Stone was discovered in 1799, leading to the eventual decipherment of hieroglyphs, which had long been a mysterious script. Their scientific observations and research resulted in the publication of Description de l’Égypte, Paris, 1809?1828, a famous multi-volume collection full of extraordinary large, copper plate engravings detailing their work. This great work gave the reader of the nineteenth century a rich and broad idea about the wonders of the great Nile Valley and its important legacy in art and architecture. A selection of these engravings from the museum’s collection illustrates the contributions made by the French scholars.

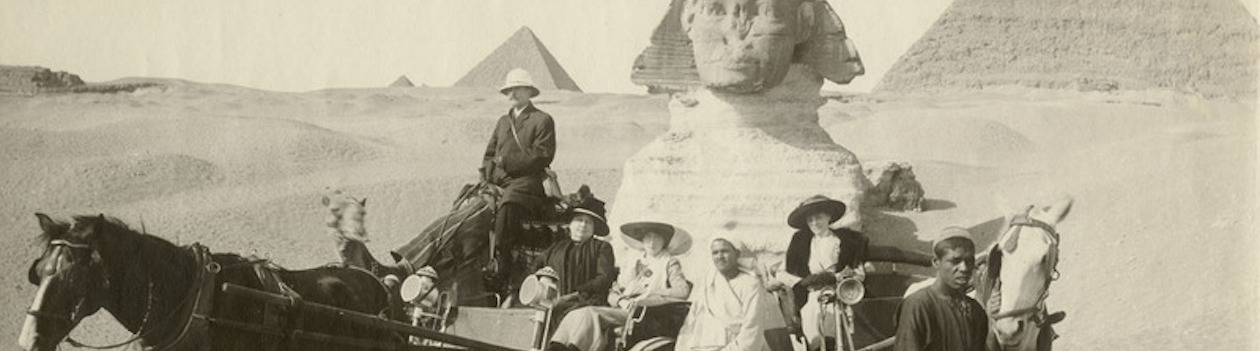

The following decades of art and design influenced by this period of exploration and minute, scientific examinations gave rise to an increase of Egyptian motifs and styles being used in art and architecture. Fashion trends as well as furnishings of various sorts were impacted. Archaeologists were excavating, Egyptologists were discovering, books and Egypt were studied, hieroglyphs were being deciphered, museums were collecting Egyptian objects, travelers were flocking to Egypt, and international expositions included Egyptian Monuments and design. Then the famous Tomb of Tutankhamen was discovered in 1922, creating another wave of interest. What had emerged was a mania for interpreting Egypt.

Egyptomania came to the United States in the nineteenth century, but much later to Tennessee. The museum exhibition displays some examples of the Egyptian Revival Style in architecture and other representations of Egyptomania found throughout the State. For example, photographic images recall the Egyptian Palace at Nashville’s Tennessee Centennial and International Exposition, 1897, and show Nashville’s the Downtown Presbyterian Church, 1849?1851, a perfect example of the Egyptian Revival Style in architecture. Other images include the Pyramid Arena in Memphis, several buildings in Tennessee designed in an Egyptian style, and cemeteries, with their obelisks and sphinxes.

Represented in three-dimensional, decorative art categories is a handsome nineteenth-century bronze and stone clock flanked by gilded female figures; a charming rug decorated with an Egyptian queen and goddess; and an elegant chess set, whose pieces are shaped as ancient Egyptian kings, queens, and nobles. The exhibition also shows Egyptomania in original memorabilia, silverware, ceramics, glass, advertisements, music, magic, and entertainment, including short film clips from movies with Egyptian themes.