The Collection

China is viewed by most in the Western world as a homogeneous country with a single culture. Its land mass is similar to that of the United States, but it is inhabited by 1.3 billion people, making it the most populous country in the world. This population is composed of more than fifty-six official ethnic groups, each with its own customs, traditions, language, foods, and in some cases, religious beliefs.

In the many centuries of China’s history, numerous ethnic groups have ruled, and each has made contributions to the art and culture of what we have come to view today as “Chinese.” In this exhibition, the museum presents a brief glimpse into China’s history, with eighty examples of art from the Han dynasty (206 BC–220 AD) to the Qing dynasty (1644–1911 AD) and several contemporary works. Panels introducing each of the dynasties provide historical, geographical, and economic background.

The Han Dynasty

(206 BC–AD 220)

The Han dynasty, the second Imperial dynasty of China, was established in 206 BC after the fall of the Qin dynasty (221–206 BC), and spanned more than four centuries, ending in AD 220. The Han dynasty is considered one of the golden ages in China’s history.

During this era military excursions increased the size of the country, and trade along the overland Silk Road greatly enhanced economic prosperity. Trade was not just conducted through intermediaries, but for the first time caravans left China and journeyed all the way to the Parthian Empire, now in the Middle East. Trade with the Middle East and India brought to China material goods, such as metalwork, and cultural influences—most importantly another religion, Buddhism.

The State guided production of iron tools, thereby enhancing productivity in farming and establishing standards for weights and measures. It also guided census taking in an effort to control households and taxation. Significant advances in science and technology included increased crop production through crop rotation and water conservation, papermaking, the nautical steering rudder, the seismograph, and a hydraulic-powered armillary sphere for astronomy. The components of gunpowder were identified, although it was not fully developed until later.

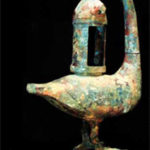

Archaeological excavations show that artisans of the Han dynasty made sophisticated contributions to material culture, including metal objects such as mirrors, lamps and containers, lacquerware (both decorative and functional objects made from wood and with many coats of resin), and earthenwares—all of which were placed about the bodies of well-to-do deceased persons in their tombs. A unique feature of some Han dynasty wealthy burials were the jade plaque suits which enveloped the bodies of the deceased. Their status was not shown in the jade plaques but rather in the gold wires and silk threads that held the jades together.

Period of Disunion: Three Kingdoms Period

(220–280), Jin Dynasty (265–420), Northern Kingdoms & Dynasties and Southern Dynasties (304–589)

The Han dynasty ended in 220 when its last emperor abdicated. More than three and a half centuries of warfare, economic instability, and political fragmentation followed, known as the “Period of Disunion.” It began with the breakup of China into three rival kingdoms, each with its own emperor claiming legitimate succession from the Han dynasty and warring with the others. Between 263 and 280, each kingdom suffered defeats, and a new dynasty was established, the Jin. But famine and invaders from the steppes to the northwest displaced millions of Chinese to the south and southeast, including the Jin emperors. In the north, sixteen unstable kingdoms ruled for approximately a century, followed by the Northern Wei dynasty formed by tribal horsemen from the northeast. Through wars, famine, and emigration, the population declined by an astounding thirty percent.

In the south, the Jin dynasty was followed by Six dynasties. The difficult times ended as China was reunified once more by the two emperors of the Sui dynasty (581–618). The Period of Disunion, while reflecting tremendous political and social upheaval, was not without positive accomplishments. There were great literary achievements (a number of emperors were themselves poets). Daoist scholars produced the first comprehensive canon of Daoist texts. Buddhism expanded and thousands of monasteries were established, along with the production of great statuary works. The Indian stupa, originally a reliquary, became the recognizable pagoda. Overland trade via the Silk Road continued to play a major economic role.

Tang Dynasty

(618–907)

In the early seventh century by uniting the aristocratic clans of all its regions the Tang Empire was established with a strong centralized state system. The empire ended nearly four centuries of division between northern and southern China and revolutionized the social and imperial structure of China.

The Tang dynasty was a period of expansion, during which much of the territory lost since the Han was regained. The Tang capital at Chang’an (Xi’an) became one of the richest and largest cities in the world, home to a cosmopolitan population of two million that included numerous foreigners. At its height, the Tang Empire stretched from what is now Manchuria in the northeast to what is now Vietnam in the south. It was a time of great prosperity enhanced by travel along both the Silk Road and sea routes. Chinese ceramics, tea, silk, lacquerware, peaches, and pears were exchanged for imported horses, spices, perfumes, glassware, and jewelry. Within China, trade between the north and the south was enhanced by the Grand Canal, constructed just before in the Sui dynasty.

Literature, scholarship, and the arts flourished. The Tang dynasty was a time of great inventions, great poets, and technologies, which influenced not only China, but also Asia as a whole. Figure painting and landscape painting took a leap forward, and woodblock printing made its appearance.

Much of what we know about Tang life has been learned from tombs where figures of people and animals, as well as implements of all sorts, were constructed of pottery to accompany the deceased into the nether world.

Liao Dynasty

(907–1125)

The Khitan people were a group of semi-nomadic tribes who lived in the valley of the Hsi Liao River east of Mongolia (modern day Manchuria). When the Tang dynasty fell in 907 and the empire was divided once more, the Khitan took control of northeastern China. Eventually the Khitan army faced that of the Song dynasty, which had taken over southern China. A treaty in 1005 between the two rulers effectively partitioned China. The Song ruler agreed to pay tribute to the Liao dynasty in order to avert war. The tribute served to urbanize the empire, expand the borders, and support a luxurious lifestyle to which the Khitan rapidly became accustomed.

The level of influence of the Khitan people on Chinese culture has been debated. They had their own script, coins, and laws. However, artifacts of the Liao period reflect similarity to artifacts of the Tang dynasty. Repoussé items of gold and silver as well as sancai (three color) glazed pottery utensils have been recovered from Liao gravesites. All religions were accepted, and Buddhism continued to flourish. Culturally, women played a more important role in Liao life than women in Chinese culture: they were seen as co-rulers with their husbands and were included in religious and other cultural ceremonies.

The downfall of the Liao dynasty resulted from the resurgence of another Manchurian group whom the Khitan had suppressed, the Jurchen. The aggressive Jurchen slowly increased in strength, and their rebellion eventually led to the Liao downfall.

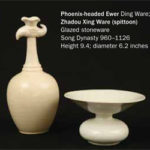

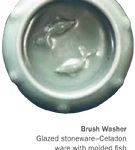

The Song Dynasty

(960–1126 Northern; 1126–1279 Southern)

The Tang dynasty ended with fragmentation into Five dynasties of consecutive ruling families in central China, and Ten Kingdoms, geographic subdivisions, in southern China. The two were unified by the Song dynasty, beginning in 960. The Song dynasty was divided into two distinct periods, the Northern Song period, 960–1126, and the Southern Song period, 1127–1279. While the northern portion of the empire was lost to the Jurchen (Jin dynasty) in 1126, the southern portion of the dynasty remained strong, as it held more of the agricultural land and the majority of the population.

The Song dynasty, often termed the most brilliant period in later Dynastic China, was a time of social and economic change that led to cultural, political, and intellectual influences extending well into the twentieth century. Politically, a shift took place from the hereditary aristocratic ruling class to a central bureaucracy of scholar-officials chosen through a civil service examination process. In contrast to the cultural and philosophical influences of the Tang dynasty, the Song period was marked by a return to Confucian traditions and thought.

Earlier innovations that became widespread in Song times include printed books, paper money, the magnetic compass, and gunpowder. Coal began to replace charcoal and steel to replace iron in weapons, tools, and construction. Southern farmers grew high-yield rice varieties from central Vietnam that matured quickly, allowing two crops per year. Maritime trade expanded in both luxury and commonplace products.

The arts flourished and collecting gained in importance. Paintings and calligraphy of the Song period captured a new spirituality and richness. One of the greatest expressions in Chinese art—landscape painting—blossomed during the Northern Song period. The simplicity and elegant forms of the earliest periods were highly sought-after and were captured in paintings, porcelains, and pottery. The pure white porcelains produced from the brilliant pure white clays of the northern mountains replaced the heavy green wares and were highly desired at court. Ding and xing white porcelains and blue-green ru wares were the prized items of the day.

Yuan Dynasty

(1279–1368)

Unifying the Mongolian tribes to form a powerful army, Temuchin was elected by the council of Mongol chiefs and given the title of Genghis Khan, “Universal Ruler.” Striking out to the east, south, and west, Mongol armies conquered Central Asia, Persia, and lands as far west as Russia, Hungary, and Poland. Kublai, a grandson of Genghis, completed the conquest of China, and although named the Great Khan, actually ruled the eastern khanate, named Yuan (“original”) dynasty.

During the Yuan dynasty, Dadu (as the Forbidden City was then known) and present-day Beijing were built. Trade between the East and the West continued to expand, fostering understanding of one another’s cultures and various religious practices. This was the dynasty during which Marco Polo visited China. While the ethnic Chinese were ostracized in many ways, they wholly embraced the arts that flourished.

The Mongols divided the population into four classes, with those of Mongol birth at the top. They were followed by the “colored eye people,” which included Uyghurs, Central Asians, and Europeans. Next came the Manchus, Jurchen, and NorthernHan. At the bottom of the list were the Southern Song Han and other southern groups. The Mongols and other non-Chinese enjoyed offices and privileges. Many Muslims from Central Asia became established as merchants and financial administrators, and Christians also enjoyed Mongol rule. The Mongols did not assimilate into the Chinese culture or learn their language. Such policies caused discontent among the Chinese and led to the ultimate downfall of the dynasty in 1368.

The Ming Dynasty

(1368–1644)

Long years of ethnic discrimination and over taxation of the Han Chinese by the ruling Mongols, massive flooding of the Yellow River, and ultimately a rebellion of Chinese from the south, brought the Yuan dynasty to an end. The new ruler, known as the Hongwu Emperor, named his dynasty Ming, meaning “brilliant.” Geographically, China under the Ming dynasty was smaller than the eastern khanate; it included part of Manchuria but not Tibet or the western area along the Silk Road.

In everyday government, Chinese scholar-bureaucrats were commonly chosen on the basis of merit and civil service examinations, without regard to family connections. Europeans appeared in ever-growing numbers in China, as ships brought new crops—maize, tobacco, and sweet potatoes—from the Americas. Ever mindful of the incursion of tribes from the north, the emperor ordered the Great Wall structurally fortified into its present form.

Not surprisingly, a major change of the Ming dynasty was a focus on Chinese culture. Ming emperors returned their attention to distinctively Chinese traditions, reinstating Confucianism, the philosophy of the ancient Chinese. The emphasis on Chinese culture produced a flowering in the arts. Ming architects produced the splendor of the Forbidden City, the emperor’s residence in Beijing. Ming porcelain, bronze, and lacquerware were coveted collectors’ items then and now. In literature, the novel appeared.

The Qing Dynasty

(1644–1911)

The Jurchen, a large group of farmers, herders, hunters, and foragers who lived in eastern Manchuria, began to expand their territory to the north and west, incorporating Mongols, immigrant Koreans, and even northern Han into their society. Calling themselves the Manchu, they conquered Mongolia and Ming China, establishing the Qing (“pure”) dynasty. The use of firearms and artillery in battle was widespread during this period. The empire was further extended when the Qing conquered the steppe region west of Mongolia.

The Qing favoring of an isolationist policy proved fatal in dealing with western foreign powers.

While Great Britain wanted Chinese silks and tea, the Qing desired nothing from them in return, causing a great trade imbalance. As a result and against Qing regulations, the British began importing opium into China from their Indian territories. This led to the Opium Wars and British success, as the Chinese greatly underestimated the strength of the British army. Waning military strength, internal rebellions, forced concessions to European countries and the United States, and usurpations of power by provincial leaders and advisors, led to the end of the Qing dynasty in 1911. On January 1, 1912, the new Republic of China was declared.

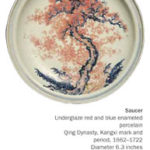

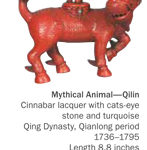

Great contributions were made in literature and the arts during the Qing dynasty, particularly during the reigns of the Kangxi, Yongzheng, and Qianlong Emperors— the period known as “The Three Great Emperors” (1662–1795). The Kangxi Emperor, a poet and excellent calligrapher, commissioned a dictionary that is still in use today. He and the Qianlong Emperor were avid collectors, commissioning works of art in many different media—painting, calligraphy, sculpture, and porcelain—unequaled throughout the world. During the Yongzheng and Qianlong Emperors’ reigns (1723–1795), the imperial kilns produced fine porcelains, unsurpassed anywhere. European techniques in enamels and metal, previously unknown in China, were learned and perfected. The sumptuous imperial summer palace, the Yuan Ming Yuan, or Gardens of Perfect Brightness, was constructed and designed in Western taste with the aide of Jesuit priests whom the Qianlong Emperor befriended. Its destruction and burning by British and French troops during the Second Opium War in 1860 was an indelible symbol of foreign aggression. With the end of the Qing dynasty came the end of perhaps the greatest period in Chinese culture and arts.

New Beginnings

(1912–present)

Although Sun Yat-sen, the first provisional president of the Republic of China, is considered one of the greatest leaders of modern China, his political life was one of constant struggle. After the success of the revolution, he quickly fell out of power and led numerous revolutionary governments as a challenge to the warlords who controlled much of the country. Increasing resentment of foreign companies, the hostilities of competing warlords, and strikes in various localities contributed to the enormous political unrest of the early twentieth century. Sun did not live to consolidate his power over the country. His Chinese Nationalist Party, or Kuomintang, formed a fragile alliance with the Communist Party that split into two factions after his death in 1925. Struggles between the two groups led to civil war and the eventual founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949 by the victorious Communists.

The New Culture Movement, “xin wen hua yun dong,” which began in the 1920s, arose from the failure of the Republic of China to address China’s problems and called for a new Chinese culture based on global and western standards. This movement went into a period of quiescence when Mao Zedong launched the Cultural Revolution alleging that the “liberal bourgeois” were permeating society. It was not until after the death of Mao in 1976—well after the end of the Cultural Revolution—that a new movement once again came to life. Contemporary Chinese art began to bloom.

Today’s contemporary Chinese art is broad in scope, some artists borrowing upon traditional methods while still others drawing upon a new explosive contemporary style, totally departing from China’s past.