by Elaine A. Evans, Curator/Adjunct Assistant Professor, McClung Museum, University of Tennessee

INTRODUCTION

…may thy ba not be repelled from what it desires….

– Dynasty XVIII

In 1991 the McClung Museum acquired by purchase from the Toledo Museum of Art, Toledo, Ohio, a number of ancient Egyptian objects, including a figure of a ba-bird (MM: 117/648). The object is made of polychromed gesso on wood, and it measures 11.5 cm long x 9.2 cm high; its provenance is unknown.

An examination of the object was undertaken and comparisons were made with similar examples in other museum collections, to determine the function and meaning of the object and the probable species represented. The results of the study show that such figures are more common after 660 BC, suggesting a late date, circa 660-30 BC, for the McClung Museum’s figure. As is the case with the Museum’s example, these figures were made of polychromed gesso on sycamore(?) wood. Although wooden figures must have been produced during earlier periods, this investigation did not find any dating earlier. Also noted was that, in publications, the ba is frequently referred to as a person’s “soul,” a term that turns out to be misleading. There is every indication that, to the ancient Egyptians, theba was the complete whole of the deceased.

DESCRIPTION

McClung Museum Ba-Bird

In our figure, the ba is imaginatively represented as a bird with a human head. As is usual, the figure rests on a slightly tapered rectangular base which originally may have been attached to the top of a wooden sepulchral tablet or shrine, or perhaps the corners of a wooden outer box enclosing the coffin. These locations suggest places where the bird might alight.

Typically, the ba-bird wears a black wig, with lappets on the chest. The wig has raised edges creating a relief effect. The face, which represents that of the deceased, is a light tan with facial details in white and black and with a brown mouth. The deep-cut body has a green back and wings, and the feathers are well detailed in black. The tail is solid black and the feet are terra cotta color. Five fine horizontal black lines on the tan-colored chest suggest a wesekh-collar, or “broad collar,” in reality usually made of beads. The chest is also decorated with vertical black strokes, or short lines, and the feathers above the legs with two horizontal lines.

A sun disk or headdress may have surmounted the head, a uraeus may have been placed above the forehead, and a chin beard may have been attached under the chin where oval sections of the gesso have broken away from these areas of the head. There is a repaired break across the feet and tail, and an undetermined hole at the proper right below the wing, between the tail end and the front leg. The painted gesso is chipped off most of the base and areas of the figure.

CONCEPT OF THE BA

More than likely the ba was not considered a duality, a composite of body and soul, or one composed of material and immaterial elements, but represented the whole of all of the deceased’s qualities.

“May it see my corpse, may it rest on my mummy, Which will never be destroyed or perish.” PAPYRUS OF ANI, New Kingdom, Dynasty XVIII, Collection of The British Museum.

The ba was not a separate being, but a powerful aspect or expression of the same person that was within the person even before birth. As the ba was not usually associated with the living, it was believed to become manifest at the time just at the point of death, before resurrection.

Equating the ba-bird with the “soul” of the deceased would be misleading. Interpretations of the ancient texts point to a different meaning. According to L. V. Zabkar, the term ba itself “has no exact equivalent in any modern, classical, or semitic language.” However, it may be that the word “animated” or “manifestation” is closest, so that “spirit” might better express its meaning. In other words, the ba was, as explained by Henri Frankfort, the deceased’s “animated manifestation as well as his animation, pure and simple — his power to move in and out of the tomb, the ‘eternal house,’ and even to assume whatever shape he wished.”

Painted reliefs depict the ba fluttering above the deceased in the tomb chamber or on its way down the tomb shaft on its return to the body in the tomb, after having flown about the marshes, fields, and thickets outside in the earthly world.

Illustrations of the bird in the McClung Museum exhibition are depicted on a painted coffin fragment and on the sarcophagus of Djed.

“…he shall go forth by day and His Ba shall not be restrained.” PAPYRUS OF ANI, New Kingdom, Dynasty XVIII, Collection of The British Museum

As an animated version of the motionless deceased, the ba possessed the power to move at any time, change its shape, go on excursions, and return to the body.

The ba of a noble and common person had the nature of a human body and performed all earthly functions. These bas of the dead represented past generations. The Egyptians, as do people of many cultures, believed people survived after death, so the ba was believed to live on into eternity.

ADDITIONAL CONCEPTS

Several other concepts concerning the ba may be mentioned here. The ba of a pharaoh, whether living or deceased, was the manifestation of the king’s special power associated with his position with the gods. Queen Hatshepsut of the New Kingdom claimed her ba was given to her by the god Amon.

Each god also had a ba, identified with the special power of that particular deity. The ba of the Apis bull-god, for example, was the manifestation of the ba of the god Osiris so that Apis had his power.

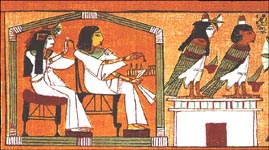

Deceased couple seated behind their bas on a temple roof. PAPYRUS OF ANI, New Kingdom, Dynasty XVIII, Collection of The British Museum

Through the bas then, the gods could become part of and communicate themselves to other gods, celestial bodies, animals, and inanimate things — and be manifested in them.

In terms of the king, the ba is explained as his great power among the gods. The Great Sphinx, representing a king, was considered “great of Bas” and therefore a manifestation of the great power of the king.

Architectural features, such as the pylons of temples as found at Karnak and Luxor as entrances to sacred precincts, and sacred writings, such as the Pyramid Texts in their divine words, also possessed the power of bas in them.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, the findings of this study indicate that the Museum’s ba-bird is typical, and to the ancient Egyptians represented the complete whole of the deceased and not a being separate from the body and having its own identify.

The body of the figure manifests the characteristics of a stylized sparrowhawk (Accipiter nisus) or a small falcon (Falco sp.). In general, however, artists emphasized the symbolic and decorative aspects of some species rather than their actual characteristics, so that the true species may never be certain. The bird form was no doubt chosen because of its ability to navigate land, sea, and air.

Although these figures were made of painted wood, the Egyptians nevertheless believed they became magically alive in the tomb. The ba-bird was a real and vital part of ancient Egyptian religious beliefs, and essential in its funerary role. There is textual evidence that the concept of the ba remained fairly consistent from the earlier to the later periods in ancient Egyptian belief. In Ptolemaic and Roman times it was said of the deceased, “May his Ba live before Osiris.”

SELECTED WEB RESOURCES

- Ancient Egypt, The British Museum

- Ancient Egyptian Concept of the Soul, by Caroline Seawright

- Book of the Dead, by Caroline Seawright