by Elaine Altman Evans, Curator/Adj.Asst.Prof., McClung Museum, The University of Tennessee, Knoxville

…thus I evolved myself under the evolutions

of the god Khepri….

– Papyrus of Nesiamsu (Ptolemaic Period)

By far the most important amulet in ancient Egypt was the scarab, symbolically as sacred to the Egyptians as the cross is to Christians. Scarabs were already known in the Old Kingdom, and in the First Intermediate Period the undersides were decorated. They were probably sacred in the Prehistoric Period and had a role in the early worship of animals, judging from the actual beetles that were found stored in jars buried with the deceased and from those found in graves during the time of King Den of Dynasty I. A scaraboid-shaped alabaster box from Tarkhan seems to confirm that the scarab was already venerated at the beginning of Dynasty I. Scarabs are the most numerous amulets and were produced well beyond the dynastic periods.

Types of Scarabs

Among the kinds of scarabs are: ornamental scarabs, heart scarabs, winged scarabs, scarabs with the name of a king or queen, marriage scarabs, lion hunt scarabs, commemorative scarabs, scarabs with good wishes and mottos, scarabs with symbols of unknown meaning, and scarabs decorated with figures and animals.

Most of the scarabs in these categories were probably used as seals, as proven by impressed clay fragments.

Ornamentation

The underside of the abdomen, or flat side, of the scarabs was usually inscribed with the names of pharaohs and officials, private names, magical mottos, formulae, volute designs and other patterns, images of deities, sacred animals, and religious symbols.

Scarabs were used by both the rich and the poor.

For the average Egyptian a simple message was provided on the scarab with no rhetoric:

- A concise simple good wish, such as: “(May) Amun (grant) a good new year”

- A name, such as: “The Lady Y-ab,”

- A motto, such as: “Firm of heart”

- A summary of their personal religious feelings in a magical prayer, such as: “Amun is strength.”

The king, noble, or official might even have a lengthy inscription, such as: “Beloved of Re, Prince of Truth, Beloved by Amun, Horemhab.”

An uninscribed scarab was probably just as sacred in the belief in its strong influences.

In many instances scarabs are valuable for the historic information they provide, such as in the narrative type, commemorative scarabs. The Lion Hunt and Marriage scarabs of Amenophis III relates events during his reign.

Nor did the power of the amulet go unnoticed outside Egypt’s borders. Numerous scarabs have been found in Palestine and other areas of the Near East, Spain, Italy, Sardinia, Greece and elsewhere, verifying the spread of Egyptian religious beliefs way beyond its borders. Most of these scarabs seem to have been accumulated as a result of contact from war and conquest, administration or trade, or through diplomatic relations.

Use

In one form, scarabs were a cheap and common form of “charm” which everyone could afford and easily wear strung on a cord on their person. Most scarabs were made for the living. The small magical object was believed imbued with particualar protective powers that warded off evil and provided good things for the owner for this life and also for the next, particularly when sewn to mummy wrappings. This was especially true when worn as a heart scarab or winged scarab to provide a safe journey into the Afterworld of the gods.

Jewelry in the form of pendants, bracelets, and necklaces prominently featured scarabs of various sizes and were all believed to possess amuletic properties. By the Middle Kingdom, scarabs were being worn on the finger mounted as a ring, or threaded with a cord for the finger. Numerous impressions on clay, bearing the names of royal and non-royal names, animal figures, and decorative motifs found on letters, documents, and containers attest to scarabs having been primarily used as seals.

Although scarabs are known from the earliest periods, it is in the 12th dynasty that their use as seals became common. The great majority of the thousands of scarab seals were quite small, generally measuring around three-quarters of an inch long by half-an-inch wide and about a quarter of an inch high. The name of a particular person, king, or official title was inscribed on their flat bases to ensure protective powers would be given to the owner and to the owner’s property. Interestingly, some scarabs with royal names were worn after the king was deceased, in the saintly sense, similar to the holy medals of Christian saints. In all probability, no matter what their category, scarabs represented sacred emblems of Egyptian religious belief.

The lock and key was unknown in Egypt. Instead, clay was shaped and impressed with seals to secure the contents of jars, bags, boxes, letters, and official documents, and to safeguard storage rooms by sealing the doors. They were handy and easily carried on the person. Official seals were so important that at least as early as the Old Kingdom officials instructed students in the art of being “sealers.” Official departments had their secular sealers such as “Sealer of the Honey,” while religious organizations had their “Divine Sealer.” In the Middle Kingdom the royal treasury had its Chancellor and “Keeper of the Royal Seal.” The idea of using a stamp seal, or “button seal,” was imported to Egypt from Asia, but in taking the form of a beetle it became exclusively Egyptian.

Although the scarab amulet may have been degraded by its utilitarian use as the everyday seal, it still retained its religious and magical importance throughout the dynastic period and later. In the Greco-Roman period scarabs were sanctified by sacred rites performed in the elaborate “ceremony of the beetle,” performed only on nine particular days of the month.

Material

From the beginning, the majority of scarabs were small, sometimes just 1 cm. long. They were mostly carved out of steatite and coated in a variety of colored glazes, mostly shades of blue or green, perhaps a color influenced by the iridescent greenish-blue of the actual beetle.

Scarabs were made in a wide variety of materials, such as carnelian, lapis lazuli, basalt, limestone, malachite, schist, serpentine, turquoise, colored glass, and alabaster. Pottery scarabs were also produced in terra-cotta molds, carved when dry and different colored glazes applied.

In Dynasty XII and later, although often undecorated, one of the materials from the semi-precious stone category that was used was amethyst. In the New Kingdom faience was especially favored. Gold and silver were used but are seldom found, probably due to theft and being melted down in early times. They were also made in cloisonné, some strung on gold wire.

Apparently knives, gravers, and simple drills were used to shape them. Softer materials were surely carved with hardened copper tools, known in the early predynastic period. During the later dynasties, tools of hardened bronze, the tubular and bow drill, were essential for soft material and also for hard stones. Flint or obsidian tools were probably favored by the engraver of delicate inscriptions.

Symbolism

The typical scarab was modeled after several species in the Family Scarabaeidae, but primarily the common Egyptian dung-beetle, Scarabaeus sacer, and its various subspecies. There were numerous variants of the sacred stout-bodied beetles. By observing the physical differences between actual beetles and the way in which they appear as scarabs, the types used as models can often be identified.

In the minds of the Egyptians the efficacy of the amulet was based on the habits of the actual beetle. The Greek writer, Plutarch (ca. AD 40-120), described their asexual perception of the beetle:

One accepts (with the ancient Egyptians), that these varieties are only male beetles, that they put down their seed substance (semen) which forms a ball and the beetle rolls it forward with its widely spaced hind legs so that the beetle imitates the path of the sun as it went down in the west and rose in the east in the mornings.

However, in reality the male and female often work together and it is the female which, after dropping her eggs in the ground, covers them in excrement on which the larvae feed. As the soft dung ball is rolled across the ground, dust and sand attached to it so that it became hardened and was sometimes equal in size to the beetle. Without a doubt in the mind of the unknowing Egyptian this was a thought provoking and impressive achievement that imitated the daily appearance of the sun. This observation prompted the Egyptians to associate the beetle with one of the many aspects of the great sun god, that of the rising sun, Khepri.

The magical sense of the scarab as an amulet was reinforced through a play on the name it was given. The Egyptian name for the dung-beetle was hprr, “rising from, come into being itself,” close to the word hpr, with the meaning “to become, to change.” The word hprr later became hpri, the divine name Khepri, given to the Creation god, who represented the young rising sun.

The name Khepri was often included as one of the five great names in the titulary of the king. Khepri was identified with the sacred beetle, Kheper, in life style and in being self-created. Khepri is often shown as a man with a beetle head or surmounted by a beetle or as a beetle. Kheper, the sacred beetle, was believed the reincarnation of Khepri, the sun-god, being reborn each morning as the young sun, newly emerged out of the earth. Khepri, with the great sun-disk before him, would be energized in the other world each morning and roll the sun disk onto the horizon at sunrise and across the sky, just as the beetle rolled its dung ball over the horizon on the earth and buried it in the sands. As the earthly symbol of an aspect of the great life-giving sun,Kheper was identified with spontaneous creation, regeneration, so closely associated with eternal existence.

A parallel idea of the god is with the newly born, completely formed beetles, which appeared to come out of the dung ball as self generated creatures springing forth full of life. According to the story of the Creation, Khepri says, “I developed myself from the primeval matter which I made, I developed myself out of the primeval matter.” This was viewed as a sign of eternal renewal and reemergence of life, a reminder of the life to come. It signified to the Egyptians the descent under the earth, in the tomb, which was only a prologue to rebirth and the endlessness of life. Life and death were in a continual cycle.

Heart Scarabs

His heart is true, having gone forth from the balance,

and he has not sinned against any god or any goddess.

– Papyrus of Ani, XXXB (Dynasty XVIII)

Not all sacred scarabs were small. The so-called “heart scarabs” were large, with an average length of 7.5 cm. These imposing amulets were placed on the throat of the mummy, on the chest, or over the heart. Some were worn by the deceased on a chain or a cord, hung around the neck, or mounted in a gold setting as a pectoral. The earliest examples came out of the Hyksos Period, the first dated to a particular King Sobekemsaf from Dynasty XVII.

This heart scarab was found on the mummy of a wab-priest of the Temple of Amun, Djed Khons-Iwef-Ankh.

Heart Scarab. Serpentine. Late Dynastic Period, Dynasty XXI-XXII.

Provenance: Thebes.

Western Reserve Historical Society: 42.192.

Many heart scarabs bear a spell on the flat side. It is a plaintive prayer to the heart of the deceased not to bear witness against the deceased when their actions are being judged before Osiris. The inscription is a version from chapter XXXB in the so-called Book of the Dead, words which provided the heart scarab with its function:

O my heart which I received from my mother,

my heart which I received from my mother,

my heart of my different ages,

do not stand up against me as a witness!

Do not create opposition against me among the assessors!

Do not tip the scales against me

in the presence of the Keeper of the Balance!

You are my soul which is in my body,

the god Khnum who makes my limbs sound.

When you go forth to the Hereafter,

my name shall not stink to the courtiers

who create people on his behalf.

Do not tell lies about me

in the presence of the Great God!

– Translation by Thomas J. Logan (1985)

Reflected in the opening lines is that the scarab was believed to be:

the heart of Isis, who was the mother of the deceased, thus identified with Horus: to be the heart which belonged to the transformations or becomings of the deceased’s future life, in order to give soundness to their limbs; and to be the charm which should ensure their justification in the judgment.

The inscription was intended to keep anything evil from rising up against the deceased and prevent any hindrance before the divine court of judgment, so that no enemy would speak against the deceased in the presence of the guardians of the balance. The spell functioned to persuade the heart not to invent lies when the heart was weighed against the feather, the attribute of the goddess of truth, Maat, on the scales during the crucial period in the court of final judgment. The heart scarab was not only the carrier of a text, it had its own function. It was a symbol of self-generation and rebirth. The ideas behind its use have been summarized as follows:

- The scarab-beetle was the symbol of the Sun-god and as such could stimulate the deceased’s heart to life.

- The scarab-beetle was the symbol of “transformations,” whereby the deceased could make any “changes” into whatever his heart desired.

- Through Chapter XXXB inscribed upon the heart scarab the deceased’s heart would not weigh too much on the Scales of Truth and in this way be accepted by Osiris.

Chapter XXXB also instructed the heart scarab to be made out of the nmhf-stone, identified as green jasper, and to be set in gold and hung around the neck of the deceased. However, only a small number of heart scarabs were completed out of this rare stone. Other green stones were abundant for the symbolic color, the sign for the resurrection, as was the gold in which it was to be set.

The large imposing size of the heart scarab contrasts with the many small steatite scarabs produced as seals and ornament. As the renowned British archaeologist and Egyptologist Sir William Matthew Flinders Petrie [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Flinders_Petrie] pointed out, the heart scarab was:

…sanctified in the xviiith dynasty by being carved in a very large size, with a purely religious text upon it, and placed in a frame upon the breast of the dead…. Such were the high religious aspects of the scarab in the later times, removing it from the almost contemptuous familiarity to which it had been degraded, as the vehicle of seals and petty ornament.

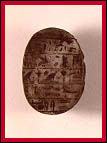

This heart scarab, possibly dating to the reign of Thutmose III (1490-1436 BC), was recovered from Tomb D120 at Abydos, during excavations under the direction of Sir W. M. Flinders Petrie.

Heart Scarab. (46K) Speckled green serpentine. Size: 4.7 cm. wide x 6.7 cm. long x 3.2 cm. high. New Kingdom, Dynasty XVIII(?). Provenance: Abydos, Tomb D120.

Oriental Institute Museum: 1896.

Heart scarabs played an important role as amulets in the funerary accessories of the deceased in the New Kingdom. They were usually carved from hard stone or made of faience or a glazed pottery. As is usual, the body of this scarab conforms to the Scarabaeus sacer; the surface of the speckled green stone is polished. The eyes and head are deeply carved on the five notched shield (clypeus). The first segment of the upper body (prothorax) and wings (elytrae) are separated by fine, carefully incised double lines around the edges and triple lines separate the wings. The legs (tibiae) are tucked underneath the body and the femora of the legs are indicated by a notch in the stone. At the body end below the wings the under body is suggested by a double row of V-shaped incised lines. The scarab has no bored hole. However, on either side under the shield are two shallow holes. Under the bend in the legs there are three shallow holes and two more above either leg. The name of the person for whom this scarab was made has been erased(?) from the upper horizontal register, and the short bottom register is blank.

On the underside is a version of chapter XXXB from the Book of the Dead. Although this spell varied and was sometimes shortened, most inscriptions on the scarab retained the basic ideas, as in the text quoted above.